In From Modern Production to Imagined Primitive: The Social World of Coffee from Papua New Guinea (2012) Paige West offers an ethnography of the social connections that coffee creates between Papua New Guineans and coffee consumers of the global West. In particular, the author focuses on the production, distribution, and circulation of coffee as a commodity as well as its relationships to neolibralization, marketing images, third party regulatory systems (organic and fair trade certification), labor, value, and political ecology.

In chapter one on “Neoliberal Coffee,” West argues that the images used to market coffee produced in Papua New Guinea are not representative of the situation for coffee farmers and others tied to the industry. These narratives conflate poverty with the primitive and perpetuate damaging narratives about indigenous people, pristine culture, and linear development from privative to modern. West points to the Dean’s Beans blog entry, where the employee recounts his experiences traveling to Papua New Guinea to set up fair trade agreements with the coffee farmers there. She asserts that,

These marketing narratives engage a set of representational practices that seem to show clear connections between “alternative forms of consumption in the North” and social and environmental justice in the South (345). However, they shoe a fictitious version of political ecology. In addition, they craft producers and consumers in ways that are equally fictitious,. These moments, the moment of consumer production, the moment of producer production, and the moment of fictitious political ecology, would not be possible were it not for the neoliberal changes in the global economy that have taken place over the last fifty years. Nor would they be possible without the growth of the specialty coffee industry. (p. 41)

As someone who not long ago regularly patronized coffee shops in Western Mass that proudly used Dean’s Beans coffee products, it was easy for me to relate to this example. West goes on to show how fair trade and organic certification “refetishize” rather than “defetishize” the labor of Papua New Guineans (p. 50). In other words, privileged western consumers are fooling themselves when they assume that their consumer choices motivated by ethical and political commitments are causing positive political action. In fact, as West demonstrates, these marketing and consumer patterns have negative material effects on the coffee producers.

I have to say that this was the most interesting book I have read in the last year, maybe longer. I thoroughly enjoyed the way West defined her meaning of neoliberalism (p. 26), unpacked how the ideological values behind coffee marketing campaigns, and made her discussion of these complex issues and her arguments accessible for a non-anthropologist like me while still situating her project in the existing scholarship. Most importantly, her book challenged me to rethink my conception of fair trade and organic certification, as well as the limits of consumerist activism.

Discussion Questions:

1. Like Tsing’s, West’s book is engaged with theories of globalization and seeks to offer an ethnography of global connections. What are some of the differences and similarities between their approaches to documenting these global connections?

2. In what ways, if any, has West’s book challenged you to rethink the limits of consumerist activism? I think of all the purchasing choices that I made that are politically or ethically motivated and that I consider part of my identity (shopping at an employee-owned store like Winco, avoiding Walmart, choosing Zoe’s over Starbucks, not owning a car, buying second hand items, buying dry food products in bulk, limiting my consumption of plastics, paper goods, and meat) and wonder how delusional I actually am. Is my faith in my “political” choices as a consumer keeping me participating in “real” political action? (Yes, I know we critiqued the concept of “authentic” change, but I still think that the concept is useful in this context.)

You ever notice how you're reading about coffee and then you check your Facebook and the number of people posting images of coffee seems to skyrocket? Yeah. It probably hasn't gone up, that number... I'm just noticing it more right now. lol -- Tiffany

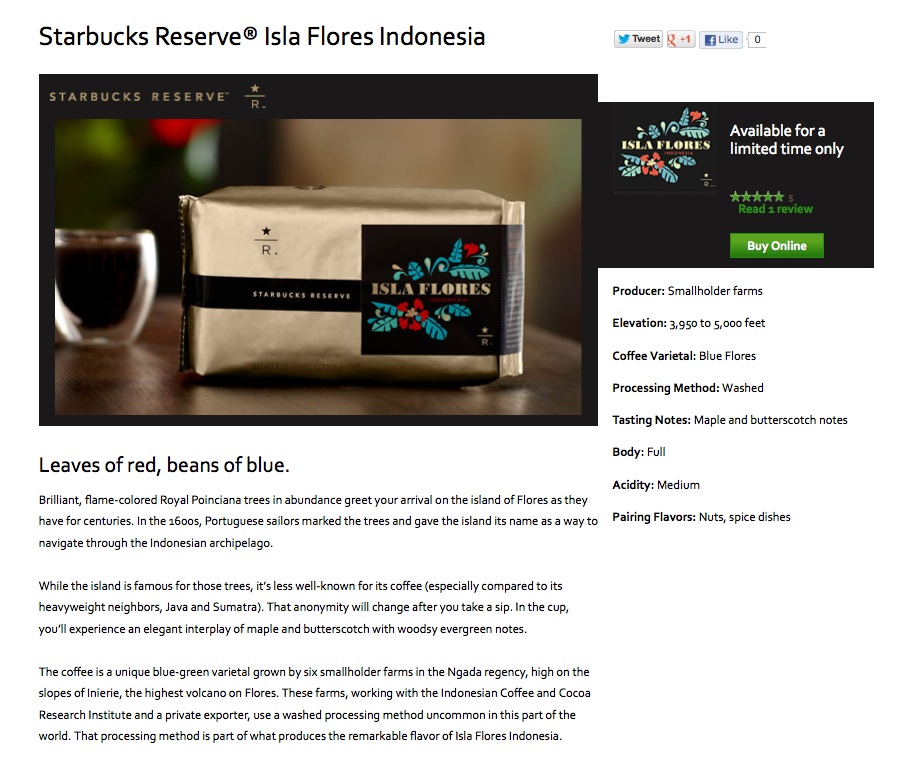

While I was reading West this morning, this ad popped in my inbox with this tag line: "exotic, rare and exquisite"...

Friction: An Ethnography of Global Connection by Anna Lowenhaupt Tsing approaches globalization from a unique, yet extremely powerful perspective. Unlike many social analyst and economist who often focus on conceptualizing globalization as a top-down rhetoric, Tsing uses ethnographic methodology to study global connections and universal aspirations (1, 4). She specifically looks at the Indonesian rainforest politics to illustrate how cultural specificity influences how global capital, universalism, and commodities are linked. She says,

There is no point in studying fully discrete “ capitalism”: Capitalism only spreads as producers, distributors and consumers strive to universalize categories of capital, money, and commodity fetishism. Such strivings make possible globe-crossing capital and commodity chains. Yet these chains are made up of uneven and awkward links. The cultural specificity of capitalist forms arises from the necessity of bringing capitalist universals into action through worldly encounters (4).

Tsing is much more interested in how universals are simultaneous productions of hegemony and resistance. And this simultaneous process, which is often contradictory, can be seen in specific cultural landscapes. Tsing pays close attention to specific cultural forms as “persistent but unpredictable effects of global encounters across difference” (3). For instance, universal local knowledge does not just operate locally, that knowledge is often mobilized across other cultures, which inevitably result in other forms of friction. By drawing attention to friction, which she argues often defines “movements, cultural forms, and agency”, she further argues that friction is a requirement “to keep global power in motion”. Tsing sees friction in specific historical contexts as important developments of universal aspirations, especially in their ability to mobilize knowledge. The three different types of universals she explores are prosperity, knowledge, and freedom, which successfully allow her to show us how friction within Indonesia keeps global power in motion as universal aspirations “travel as an ethnographic object” (7).

Questions:

1. I was really interested in Tsing’s discussion of the frontier, but more specifically the role of hyper-masculinity, as both fueled by anxiety and virility, and one way we see that masculinity assert itself is in the exploitation of women’s bodies. Tsing says:

“women can be resourceful too, and prostitution brings new resources to the frontier. But this is a world formed by an intensive peculiar, exaggerated masculinity. This is a masculinity that spreads and saturates itself with images and metaphors, amulets, stickers of naked women, stories based on the confusion between rape and wild sex. Its moving force is perhaps best seen in the imaginistic effects of the “water machine,” the high-pressure hydraulic pump, small enough for one man to carry and connect to any local stream, but whose power in the spray emerging from the taut blue plastic piping can gauge a hole four feet deep into the land and thus expose the gravel underneath the clay, gravel mixed, perchance, with small flakes or nuggets of gold. What a charismatic force! And what possibilities it unveils.” (39-40).

Now, I don’t know if Tsing is specifically making the connection that these men’s masculinity is defined by the “water machine” era, which has inflicted for miners and loggers, no matter their culture, a drive for profit and what keeps these men enthralled in this process is the image of the sexualized woman, who is submissive to men’s desires. I may be wrong, but I am interested in discussing your own reading of the quote above because I think there is an interesting relationship between masculinity, gendered and racialized violence, and labor in the frontier. What do you think?

2. I was a little confused with Tsing’s discussion of “conjuring of scale”. I think breaking it down in class will be very helpful to me in order to see how frontier extraction relies on it. Therefore, how can we conceptualize “conjuring of scale” in our own words? And how does frontier extraction rely on the conjouring of scale?

Anna Lowenhaupt Tsing’s 2005 Friction: An Ethnography of Global Connection reimagines conceptions of global connections by focusing on “zones of awkward engagement” (xi). Drawing from her anthropological work in Indonesia, specifically the Meratus Mountains of Kalimantan, Friction refutes the homogeneity of Globalization—a concept that she sees to be simply encouraging the “dreams of a world in which everything has become part of one single imperial system.” (xiii) Instead, Tsing stresses the importance of cultural difference by putting questions of “distress center stage rather than trying to avoid it” (xii). According to Tsing, contemporary views and advances into Globalization Theory are quite misleading to the concrete realities of localized spaces and histories:

Most theories of globalization, for example, package all cultural developments into a single program: the emergence of a global era. [Asking] If globalization can be predicted in advance, there is nothing to learn from research except how the details support the plan. And if world centers provide the dynamic impetus for global change, why even study more peripheral places? (3)

Seeking to go beyond dominant narratives of Globalization, Tsing refutes the advances of globalists such as Friedman and Fukazawa and finds it infinitely more productive to view global connectivity through the metaphorical lens of friction. This serves as a reminder that “heterogeneous and unequal encounters can lead to new arrangements of culture and power” (5). Tsing’s metaphor of friction is applied throughout her ethnographic study of Indonesia’s forest industry, and its political-economic-cultural dimensions. She does so to trace the historical legacies of power, difference, and culture regarding the rise of New Order Indonesia and the ecological destruction that ensued in the late twentieth-century. More significantly, Tsing finds that friction—the grip of worldly encounters—is a helpful way to understand universalisms: prosperity, knowledge, and freedom. Ultimately, Friction (2005) seeks to erase the binary constructs that dominant globalization theories have alluded to and instead makes the claim that difference is at the heart of global connections; as a result of these culturally produced differences, friction should be viewed as “the fly in the elephants nose” (6).

Interested in complicating understandings of universalism—specifically claims centered on prosperity, knowledge, and freedom—Tsing asks: “How can universals be so effective in forging global connections if they posit an already united world in which the work of connection is unnecessary?” (7) Rather than giving credence to –isms that perpetually assume to have all the answers (capitalism, globalism, environmentalism, conservatism, liberalism, etc.), Tsing’s Friction realigns abstract notions of universalism by telling the “story of how some universals work out in particular times and places” (10). Focused on narrating the dimensions of Indonesian youth, Tsing finds it imperative to study the specificities of cosmopolitanism in order to fully grasp the “cultural analysis of knowledge” (122). Her case study of Indonesian nature lovers--pencinta alam--then, provides a means by which to study global dimensions of inner connections and location (122).

It was helpful to read about the development of this student identity formation, as influenced by the political aspirations of Indonesia’s first president, but also via the youth movement’s historical genealogy. As invested as I am in student movements, reading about Indonesia’s very own youth movement was very insightful. Tsing’s theory of global connectivity revealed multi-layers of how power, resistance, and hegemony worked throughout the 20th century youth movement. Tsing’s metaphor of friction was particularly evidenced to me in her description of the relationship between the Kopassus and the pemuda; (128) particularly the ways that the youth student groups connected with the elite military guard. Similarly, the ways by which identity formation, rooted in desire and collaboration, provide a meaningful framework to conceive of student organization as anything but agents of political change.

Discussion Questions:

1) Using her conceptual framework of friction to better understand the local, national, and global connections between entrepreneurs, politicos, and grassroots movements, does Tsing allude to a difference between a politics of resistance and a politics of refusal? Or better yet, is there a difference between the two?

2) Writing about the student Nature Lovers, Tsing characterizes the group to be one of identity-formation based on national anti-politics; middle-class distinction; domestic adventure tourism; consumer culture. Writing about the intricacies of capitalism, Tsing acknowledges:

“Both domestic and foreign companies began to see the potential of advertising using images of nature lover activities: They could show young active people challenging the world with the help of their brand-name products.” (131).

Would you consider this to be similar to what Rosemary J. Coombe (1998) found to be the appropriation of counter-cultures?

Anna Lowenhaupt Tsing's Friction: An Ethnography of Global Connection (2005) explores the notion of "friction" as it can be applied to what has previously been considered "frictionless" by many scholars – particularly, the progress of globalization. Tsing makes several points about the global connections that have and continue to be made: 1) that these connections are not linear, as from central nodes of power outward, but instead are chaotic; 2) and that these connections are not simply top-down constructions from North to South, but that the global South is an active agent in constructing global scenes; and 3) that friction is not just present but necessary, as when she says, "Friction is not just about slowing things down. Friction is required to keep global power in motion" (6). For Tsing, it is important to study not only how the global North operates in a contested area but also to analyze how indigenous peoples contribute to the instability of these contested areas and create new cultures that speak not only to specificity but also to so-called universal notions.

Tsing uses ethnography to look not simply at the specific locations in which she is active, but to engage universals, ultimately making the point that it makes little sense to study universals and particulars as discrete entities but to analyze how the interplay between particular and universal "moves" global concepts and goals. She notes that her own projects with environmental activism in Indonesia "deploy the rhetoric of the universal even as they shape its meanings to their particular processes of proliferation, scale-making, generalization, cosmopolitanism, or collaboration. They require us to follow calls to the universal without assuming these calls will foster the same conditions everywhere" (267). That rhetoric of the universal, she says, is necessary on some level, even when (or, rather, especially when) the subjects in a particular location do not exactly agree on what that universal entails. For Tsing, it is important to see how different agencies – local, national, international – use universals and how those uses shape local politics of difference.

One aspect of Tsing’s work that intrigues me (or, to use the vernacular, "blows my mind") is her discussion of scale-making. Scale-making, she argues, is not neutral; rather, "scale must be brought into being: proposed, practiced, and evaded, as well as taken for granted. Scales are claimed and contested in cultural and political projects" (58). Rather than one globalism, there are overlapping "globalisms," and the same is true for the regional and the local. As I understand it, the rhetoric of the universal as used by one group (North, for example) attempts to set the scale in a particular way, but in doing so, it ignores or dismisses or neglects contesting or collaborative rhetorics that would make the global seem less "frictionless." But, as Tsing says, that interplay between different ideas about universal concepts is what can make social movements more successful.

In her analysis of the various ways that people interpret "conservation" in Indonesia, she shows that while different groups may have very different definitions and goals for a particular location, they are collaborative agents in creating a global measure that contradicts (but still improves upon) the supposedly seamless process of globalization that would otherwise not take into account local particularities. Thinking about how scale is produced (rather than taking it for granted) helped me to understand better, I think, the politics of friction in a global community.

Discussion Questions:

1) In discussion commodification, Tsing uses the example of a lump of coal that is, at each stage of its commercial journey, "appraised for different properties" and, in order to remain a sellable object, "it must be ready to meet these varied demands" (51). How does this process change in order to work for intangible commodities? Who does the appraising, and how is the "worth" of particular intangible commodities established?

2) Tsing talks about friction as a useful element in collaboration. "Parties who work together may or may not be similar and may or may not have common understandings of the problem and the product. The more different they are, the more they must reach for barely overlapping understandings of the situation" (247). I wonder if there is a line that must, at some point, be drawn in order to achieve any kind of progress? I realize that other social justice or activist movements have different elements that change the nature of the question, but if Tsing is speaking generally on this point that collaboration should contain an element of friction in order to be truly progressive (if not successful in the way that some activists consider the term), then I question, generally, whether large amounts of friction are truly beneficial. (I do so the point, though, that some friction can be productive.)

I am writing this from the lovely warmth of my childhood home as the WSCA conference I am attending is taking place only an hour from where I grew up. For some reason, the Internet at my mother's house is dinosaur-slow, even though she has DSL. I hope this successfully uploads and please know that I will be with you in spirit during class. See you all next week. ~Rachel

In Friction: An Ethnography of Global Connection, Tsing (2005) examined how the concept of friction can be applied to examine global connections and interconnections. By specifically looking at both local and global interactions within the rainforests of Indonesia, Tsing (2005) complicated the notions of both universals and particulars within globalism. Specifically, universals can be seen as tools that reinforce hegemonic power structures while simultaneously providing mobilizations for empowerment amongst the powerless. Tsing (2005) examined this and other frictions within three parts of the book: prosperity, knowledge and freedom. In the end, Tsing (2005) concludes that the examination of the repressions and struggle for justice that happen simultaneously within localized globalization must take place within it, at the point of friction, rather than from the outside vantage point that is so frequently used in academia.

One of the things that struck me the most about this book was how the notion of friction is applied to the notion of global flows. As I have talked about previously in class, I am interested in Appadurai’s “–spheres” within globalization. While Appadurai did not intentionally mean to make the flow of globalization seem smooth and seamless, Tsing (2005) articulates these flows in a dynamic and nuanced manner. The friction she applies to these situations show us that the metaphor of flow is incomplete. Like the flow of water in a river, the flow of information, culture, assumptions, technology and ideologies do not travel unimpeded. Rather, there are rocks, bends, waterfalls and branches that reroute, change and influence the flow. What is so interesting is Tsing’s (2005) proposition to not try to necessarily fight this friction, but to give into it. This actually reminds me a lot of Bhabha and Rowe’s notions of “in-between-ness.” As Tsing (2005) said, the best vantage point is inside.

Questions from the reading:

1. I am interested in this notion of universals and particulars. Is this a concept that can be translated to other aspects of cultural studies?

2. I feel like there is a connection between the hybrid spaces of Castell’s social movments and Tsing’s frictions within globalization. Am I the only one, or is there more to be said about this “middle ground” approach to critical cultural studies?

References

Tsing, A. L. (2005). Friction: An ethnography of global connection. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press.

In the book Friction: An Ethnography of Global Connection (2011), Anna Tsing uses the term "friction" as a metaphor to describe the differences that come up and structure the contemporary world through the political, social, and economic realm. She challenges the widespread view that globalization invariably

signifies a "clash" of cultures, and develops friction in its place as a metaphor for the diverse and conflicting social interactions that make up the contemporary world. In her attempt, Tsing aims to answer questions about global connectedness. Her main argument is based on her fieldwork in Indonesia's rain forest industry and its environmental and political engagement during the 1980's and 1990's. She seeks to answer the questions "Why is global capitalism so messy? Who speaks for nature? And what kind of social justice makes sense in the twenty-first century?" (p. 2). She answers these questions in her book through a series of metaphors she argues are universal truths; Prosperity, Knowledge, and Freedom. Tsing challenges these universals, as she believes globalization is not about homogenizing the world but instead understanding that

we are actually not all the same. Tsing writes, "The specificity of global connections is an ever present reminder that universal claims do not actually make everything everywhere the same….we must become embroiled in specific situations. And thus it is necessary to begin again, and again, in the middle of things" (p.1/2). Tsing points out that these differences and disparities keep global power in motion. Treading outside of localities, Tsing uses environmental politics to see how well universals work in tracing global connections. She describes how in the 1980s and the 1990s capitalist interests increasingly reshaped the landscape

of Indonesian rainforest, through chains of legal and illegal entrepreneurs who extorted the land from previous claimants, creating resources for distant markets. In response, environmental movements arose to defend the rainforests and the communities of people who live in them. Her description shows that the

social drama of the Indonesian rainforest was not only confined to a village, a province, or a nation, instead it included local and national environmentalists, international science, North American investors, UN funding

agencies, mountaineers, village elders, and urban students, among others--all combining in unpredictable, messy misunderstandings.

I love Tsing's work and her use of the framework of scapes proposed by Arjun Appadurai (1996) for exploring disjunctures. To pick one particular section, I would say, I really liked the second chapter The

Economy of Appearances. Tsing very efficiently uses Appadurai's theory on finance-scapes (Appadurai, 1996), as she traces the global capital exchange. In her description of the Bre-X speculation and failure, she shows how the collaboration of several groups (foreign investors, migrant workers, political forces, etc.) who come together to demonstrate imagined "economy of appearance" could so easily conjure speculated richness through collaborative, yet misinterpreted, work (p. 57). I think this is a perfect example of Appadurai's concept and even though Tsing's analysis of "friction," disruption and conflict does not offer answers to the issues, she recognizes its differences. She writes that at every level for the New Order of Indonesia, confusion exists even with their mix of investors, citing how foreign is domestic, public is private that further adds to the corruption.

Questions:

1. Reading Tsing was very valuable in terms of my project proposal. However, as I strive to narrow down my focus on my research proposal, I cannot help but wonder what can be some other ways of understanding activism and interpretation apart from mainstream ethnography. Is ethnography the only

way out to understand activism?

2. "Universal reason of course was best articulated by the colonizers. In contrast, the colonized were characterized by particularistic cultures; here, the particular is that which cannot grow" (p. 9). I am not sure

that I understood this line well, but I was wondering, is she critiquing the definition of universal reason from the colonizers perspective here? Or does she neglect the alternate idea of civilization (which apparently absent in the colonies) and the gradual replacement of it by the concept of culture?

3. I must admit, Tsing was not an easy reader and therefore it left me wondering about the audience of her work. Is it only targeted to a group of qualified academics? How far stretched are their capabilities to bring about change. Will the academicians be able to influence policy planners, foresters, ecologists, or taking a step backward I would like to know are they (policy planners, ecologists, etc.) even the most important

target to bring about change?

References

Appadurai, A. (1996). Modernity at large: Cultural dimensions of globalization (Vol. 1). University of Minnesota Press.

Tsing, A. L. (2011). Friction: An ethnography of global connection. Princeton University Press.

Anna Tsing's book "Friction" is a fine example of Bhabha's hybridity in the slippages between cultural tropes. Environmentalist hopes and dreams are tattered in the present world. The failure of the USA to combat global warming for one great example. Her ethnographic work was especially meaningful in light of the global development going on. As the big global picture is made of many little enclaves, her exposure of the inner workings of capital, province, village, in her final chapters was right on. She brought to light the student nature lover's ties betwixt the villagers and the cosmojetset environmental movement working to change the direction of one little portion of the Island's forest with provincial and capital governments. On the ground reporting is always more revealing than media blurbs put out by organizations with axes to grind. Tsing's axe was very sharp in cutting through the mess made by current western development. The replacement of swidden agriculture with monoculture is especially disturbing when the people are considered in context. Her method of reading the different levels of hierarchy involved brought the whole picture into focus, especially her list of species. That was particularly significant to me, as I am very concerned about the disappearance of species, especially indigenous humans, resulting from wanton clearcutting. As the rainforests go away to be replaced by single species propagation of crops and grazing lands, monoculture forestry and the toxic refuse of environmental damage the carbon sinks that have kept our biosphere a living thing go away, too. What to do about it is the question. Organizations that claim to be helping are constantly hitting on me for money, including all the big NGO names in environmentalism. As they siphon away the dollars of concerned people in the North to spend on their corporate agendas, real progress in the fight against rampant, over the top development of the South continues to wain. What can the concerned citizenry of the western democracies do to stem the capitalist rape of our planet? The ideology of profitmaking on the backs of indigenous peoples is deeply embedded in the global economy. America is especially guilty. Tsing didn't carry the attack to the USA with the kind of vigor I would expect. It is the policies of the USA that leads the international phalanx against big N Nature. Meanwhile, little n nature is swindled out of her natural resources. The United Nations seems to be complicit, and powerless. The western democracies will do nothing. The developing environmental monster, China, continues to pollute the world. No end in sight. It is disheartening to say the least. The glimmer of hope that "Friction" offers in her exposure of the dynamics between the tangled human hierarchy with indigenous villagers on the bottom and Capitalist investors on the top, and in between the bureaucracies, environmental activists and nature lovers trying to do something in this cauldron is running out of time. This slow progress in tiny pinpoints on the global map is not encouraging. Trying to think of something positive to say I can only come up with the fact that Tsing cites Kimberly Christen (2004) in note 5. That is hopeful.

Question: Should I support environmental/corporate NGOs like Sierra Club and Nature Conservancy, when they seem to be fundraising fronts and corporate shills? Question: Will the end of our marvelous biosphere come sooner than we think? Question: Can we intellectualize this away?

In An Ethnography of Global Connection (2005), Anna Lowenhaupt Tsing explores power struggles over Indonesian rain forests as sites of friction, which she defines as “the awkward, unequal, unstable, and creative qualities of interconnection across difference” (p. 3). Tsing’s methodology is ethnographic and her analysis is grounded in the narratives gathered while doing field research in rural Kalimantan. Specifically, Tsing focuses on Indonesia’s national environmental movement of the 1980s and early 1990s.

As we discussed last week in class, although Tsing studies very specific global connections that relate to deforestation in Indonesia, her book is also a study of globalism, global capitalism, and liberalism. Tsing offers a theory of globalization that challenges previous scholars’ understandings of economic and cultural change (i.e. globalization) as spreading from global “centers” outwards. Rather, Tsing demonstrates how capitalist systems and ideologies of liberalism emerge locally in peripheral places out of the frictions of global connections.

Although Tsing’s analysis really came together in part three on “Freedom,” I found her study of the nature lovers in part two particularly interesting. Tsing describes how the nature lovers, or pencita alam, and the networks they formed take international ideologies of nature and make them local – redeploying that knowledge to formulate an historically-situated cosmopolitan nationalism. The chapter describes the nature lovers’ complex relationships with student resistance movements and the military, their cultural distinctions between the rural and the urban, and their identity as consumers of outdoor equipment and – my personal favorite – Philip Morris cigarettes (p. 141 -146). This part of the book was noteworthy because it provides a detailed illustration of Tsing’s argument that “we know and use nature through engaged universals" (p. 270) and more broadly that globalization always manifests itself through local, fragmentary frictions.

Discussion Questions:

1. Like Castells, Tsing states that her research is motivated by a desire to know what kinds of social justice (or social movements) make sense in the 21st century. Also like Castells, she investigates global connections and social movements that attract the participation of social actors with diverse goals and ideological motivations. What are some connections that you made between these two texts as you were reading this week?

2. I like the idea of a project that would combine Castells’ focus on networked social movements and Tsing’s careful analysis of global frictions. What might such a project produce?

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed