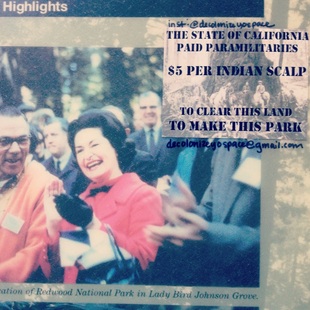

- How does Native graffiti work to interrogate colonial cartographies of territory?

- What kind of spaces do Native graffiti praxes weave together in their expressions of indigeneity and spatialized resistance?

- How can understanding Native graffiti as an anticolonial remapping technology aid in larger projects of decolonization?

RSS Feed

RSS Feed