apologies this is a little late--I made the terrible mistake of typing my response directly in here, and lost everything when I tried to upload it! forgive me if it's not quite so eloquent as the original...

Paige West’s From Modern Production to Imagined Primitive offers a detailed and thorough exploration of the ways in which social meanings and relations are constructed via production and consumption of Papuan coffee. I’ll admit I was already somewhat familiar with her critiques of US/European consumers (there are many points in the text that echo the documentary Black Gold, which is a similar treatment of coffee production in Ethiopia), but I was fascinated with her examination of the complex ways in which Papuans themselves—farming communities, “middlemen,” factory workers, etc—create social meaning through their relationship to coffee.

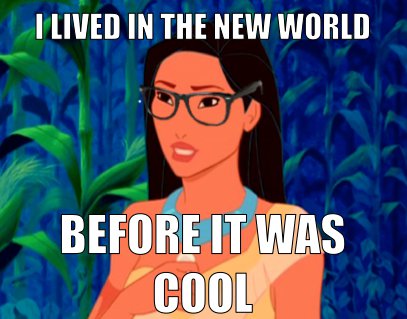

Surprisingly enough, the latter half of the text reminded me of Hipster Pocahontas—a creative and humorous iteration of the ever-popular internet meme with the goal of interrogating colonialism (I will say that to compress an appropriated racial stereotype combined with yet another stereotype of obnoxious privileged settlers in one single image to make a powerful statement on colonial occupation is pretty brilliant). It seems particularly ironic that wealthy European consumers are demanding that Papuans modernize by farming organic produce, as if non-organic farming wasn’t an imperial-colonial imposition in the first place. Like Hipster Pocahontas, Papuans went organic before it was cool! I think images like these are a really great bridge to West's implications and some of Coombe's interventions--I would love to see a series of images retooling/reappropriating the images of indigenous Papuans that are so common on organic coffee packaging in the spirit of Hipster Pocahontas to make a comment on Papuan experiences of colonialism.

I was also reminded of a selection from Maori scholar Linda Tuhiwai Smith's classic test, Decolonizing Methodologies: Research and Indigenous Peoples--

I was also reminded of a selection from Maori scholar Linda Tuhiwai Smith's classic test, Decolonizing Methodologies: Research and Indigenous Peoples--

The real critical question in this discussion relates to the commercial nature of knowledge ‘transfer,’ regardless of what knowledge is collected or how that knowledge has been collected or is represented. In this sense, the people and their culture, the material and the spiritual, the exotic and the fantastic, became not just the stuff of dreams and imagination, or stereotypes and eroticism, but of the first truly global commercial enterprise: trading the Other. This trade had its origins before the Enlightenment, but capitalism and Western culture have transformed earlier trade practices (such as feudal systems of tribute), through the development of native appetites for goods and foreign desires for the strange; the making of labour and consumer markets; the protection of trade routes, markets and practices; and the creation of systems for protecting the power of the rich and maintaining the powerlessness of the poor. Trading the Other is a vast industry based on the positional superiority and advantages gained under imperialism. It is concerned more with ideas, language, knowledge, images, beliefs and fantasies than any other industry. Trading the Other deeply, intimately, defines Western thinking and identity. As a trade, it has no concern for the peoples who originally produced the ideas or images, or with how and why they produced those ways of knowing. It will not, indeed cannot return the raw materials from which its products have been made. It no longer has an administrative Head Office with regional offices to which indigenous peoples can go, queue for hours and register complaints which will not be listened to or acted upon.

Has the Papuan coffee West studies become another form of trading the Other? Are the images and ideas sold with the coffee a consumable product? I found myself elated to read that the members of the community West was working in began to demand compensation from tourists who were photographing them--from this perspective it seems obvious that is the very least that's owed them. This, however, this brings us back to Coombe (particularly our conversation on the Atlanta Braves)--what is at stake in these kinds of social-capital flows? What are the ramifications of individualistic survival/profit on a colonial racial stereotype?

Discussion Questions:

- Throughout the latter half of the text West delves into the specifics of how both producers and consumers of Papuan coffee construct material social realities and spatial imaginations through their relations to said Papuan coffee—how can this complicate our understanding of globalization and transnational interconnection?

- West mentions that she is concerned about what will happen when millennials no longer have interest in the alleged wellbeing of the primary producers of the products they consume (eg Papuan coffee farmers)—considering the broader imperial-colonial landscape things like Papuan coffee cultivation are embedded in, is this a major concern? Should we be worried about would happen if and when the essentialized primitive romantic Indigenous Laborer is no longer trendy? Do you foresee a future in which that occurs, or will commodification and exploitation of indigenous bodies continue albeit perhaps in new spaces and forms (perhaps in the vein of Black Gold)?

- West’s assertions re: the imagery sold alongside organic coffee has strong connections to some of the themes present in Coombe’s text—namely commodification of indigenous bodies, essentialism and appropriation of indigenous cultures, and the larger stakes of public battles over signs and meanings. How can Coombe’s text help us to understand the images of an essentialized primitive indigenous Papuan on coffee packaging? Can we imagine a space allowed to indigenous peoples in which it is possible to both mobilize public ignorance and survive/profit off a distinctly indigenous product without furthering more violence (eg Tanka Bars)?

RSS Feed

RSS Feed