Author's note: Because my computer thought it would be funny to make me work more, Safari crashed when I uploaded the original draft of this. As such, this is the second iteration of this specific paper. I apologize that it isn't nearly as good as the first, but there is a moral to this story: save your drafts, folks! ~Rachel

In the Cultural Life of Intellectual Properties: Authorship, Appropriation and the Law, Coombe (1998) examined the role of authorship and intellectual property vis a vis cultural appropriation within the framework of the law. Specifically, Coombe (1998) used multiple cases of trademark, celebrity, logos and advertising to make the argument that law both engenders and endangers how different individuals, groups and cultures uses these signifiers as points of resistance. Coombe (1998) argued that law has for too long thought of issues of trademarking, intellectual property rights and copywriting as being detached and/or abstracted from the concrete reality of the cultures and societies from which these laws were created. Using a "critical cultural legal studies" framework that draws heavily from postmodern Anthropological studies, Coombe (1998) relatively successfully sought out to connect the abstractions of law to the concrete realities that it is applied to. Within these connections of the abstract with the concrete, Coombe (1998) also dismantled the notion of the "Romantic author" with respect to art and Culture. Throughout the book, Coombe (1998) continually made a persuasive case for creating "...an epistemic shift in our understanding of intellectual properties" (p. 39).

There were several aspects of Coombe's (1998) overall argument that I found interesting. There was one that I am specifically interested in examining closer: her interpretation of the prosthetic body within the public sphere. Specifically, Coombe (1998) made the following observation:

Through the use of trademarks the bourgeois subject was able to secure privileges for his otherwise

unmarked identity, provided that he marked his prosthetic self with a recognizable signs of distinction;

commercial privilege might be marked by the corporeal indicia of publicly recognizable social others. (p.

172)

It is interesting to note that Coombe (1998) is relying heavily (to borrow her term) on Berlant's conceptualization of the prosthetic body. However, in Coombe's (1998) inclusion of Berlant's concept of the prosthetic body, there was the exclusion of Warner's (1992) own conceptualization of the prosthetic body. In Warner's (1990) articulation of the prosthetic body, rather than the body being seen as something that is to be used to secure privilege through specific marking, it can actually be seen as a "blank slate" of sorts. Specifically, Warner (1990) referred to the use of text as a prosthetic body where all of the marks of whiteness, maleness and heterosexuality that would exclude those who did not have them were rendered "invisible." Therefore, those who were Othered were able to enter the public sphere as an equal to everyone else. This interpretation of the prosthetic body has once again gained salience within the virtual realms of the Internet.

This critique of Berlant via Coombe's (1998) conceptualization of the prosthetic body is incorrect or misguided, but rather as a way to help strengthen Coombe's own point that often meanings, authorship and appropriations are contextually bound and unstable. For Coombe (1998) the concept of the prosthetic body as a tool for the bourgeois is contextually appropriate for her argument. For my own research on the formation of identities within the virtual realm, Warner's (1990) concept of the prosthetic body being a blank slate is contextually appropriate. In the end, this departure of conceptual meaning within different contexts proves Coombe's (1998) point that there needs to be a concrete reality check for the abstractions of law.

For discussion:

1. In chapter two, Coombe (1998) discusses how prosocial interactions between celebrities and their multiple authors create ruptures within the dominant discourses surrounding the performativity of gender and sexuality. What other examples can we think of (beyond camp and pastiche) where individuals have reappropriated a celebrity as a means of rupturing gender and/or sexual norms within society?

2. Coombe (1998) pointed out that the laws surrounding the exclusive property rights of celebrities will create a stagnation for future generations of performers and artists. Specifically using Madonna as an example, Coombe (1998) details the ways in which Madonna as the performer is created from a bricolage of previous stars and icons that came before her. However, since Madonna has now copyrighted and trademarked every part of her image, future performers will be limited in how they can appropriate what was already appropriated by Madonna. My question however, is then how do performers like Lady Gaga, who amongst other images and icons, has drawn heavily from Madonna able to get away with her celebrity while other performers get sued?

References

Coombe, R. (1998). The cultural life of intellectual properties: Authorship, appropriation, and the law. Durham, NC: Duke University Press.

Warner, M. (1990). The letters of the republic: Publication and the public sphere in eighteenth-century America. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

Warner, M. (1992). The mass public and the mass subject. In C. Calhoun (Ed.), Habermas and the public sphere. Cambridge, MA: Massachusetts Institute of Technology Press.

Rosemary J. Coombe's The Cultural Life of Intellectual Properties (1998) addresses the connections between hegemonic Western legal discourse surrounding intellectual property and the cultures of commodified images. As law is thought of as neutral and abstract (disembodied) and when cultural scholars were (are?) ignoring the impact of law on daily embodied lives, Coombe argues that law and culture are not discrete, bounded entities, that they shape each other and affect how subaltern communities attempt to produce agency.

One of Coombe's goals is to use examples to disrupt the notion that law is a neutral agent and emphasize its structure as rooted in European Enlightenment ideals, which include the notion of the Romantic author and an object in the public realm being considered as private property. She also uses these examples to show how some meaning-makers are able to use the forms embedded in intellectual property law to produce a kind of “counterpublicity,” which involves “articulations that deploy consumer imagery and the bodily impact of the trademark to make the claims of alternative publics and other(ed) national allegiances (184).

Among the various components of this necessarily complicated argument, Coombe brings up points of contention that anthropologists and cultural studies scholars (and, since I’m a folklorist, folklorists) have been arguing for decades: authenticity, tradition, liminality. Coombe works to break down the notion of authenticity, claiming (as other contemporary anthropologists/cultural studies scholars/folklorists are doing) arguing that claims to authenticity “embody contingent concepts integral to Western histories of colonialism and imperialism” (215). In Chapter Five’s discussion of the debate over the ability of white authors in Canada to “create” Native (or other subaltern) characters in fictional works, the arguments against “censorship” and “free expression” on one side come up against arguments about lack of authenticity on the other. But both, Coombe argues, perpetuate the notion of culture as a unitary concept as well as of ideas (or expressions of ideas) that can be “possessed.”

Also with regard to authenticity, Coombe notes that arguments within legal constructs that revolve around the notion of authenticity both essentialize and erase living Native peoples (a practice with a long history in American myth making). Thinking in particular about the Washington Redskins and other professional sports teams, the logos and behaviors of spectators perpetuate a unitary notion of “Indian” that effaces not only the issues Native communities efface but their very bodies. While the battle over sports team logos has been going on for some time now, Coombe notes that, on the professional level, not much real progress has been made, despite the notion of counterpublicity that could potentially produce negative publicity for sports teams owners as well as keep the discussion of racism against Native peoples in the public eye (199).

For Discussion:

How can we connect Coombe’s ideas about authorship to Boyle? Specifically, are there differences in how they conceive of romantic authorship historically? How does Coombe’s use of ethnography complicate or expand upon the critical theory of culture and law that she discusses?

Coombe discusses the conflict behind the methodology of using “proprietary counterclaims” (204) as a way of attaining some form of agency in dealing with the hegemonic Western legal system. Framing these counterclaims as theft of cultural property rather than “assertions of harm” (204) becomes a case of trying to tear down the master’s house with the master’s tools. Coombe notes Handler as saying that such a strategy of using “a language that power understands” is a necessity in order to gain any political power (or even presence) at all (242). Considering her last discussion of free speech/free expression, is an ethics of contingency feasible?

In looking at cases such as the Washington Redskins and others, what is the “usefulness” of counterpublicity as a tactic for transformative social change?

great work this week so far with Coombe! As I promised, there is more than enough theory and application to keep us busy in class. So please post up here any and all extras we might watch, listen to or look at to extend our discussion of Coombe's critical legal theory...yes, the THEORY!!

(Post by Rachel) As I was reading through Coombe's chapter two, I was more than amused by the thought of Judith Butler fanfic. Doing a little (emphasis on little) detective work online, I found digitized copies of the two editions of the zine. You can find the first edition here and the second edition here. I will admit that I did laugh, especially in when faced with the juxtaposition of gay male bondage advertisements and an "interview" with Gayatri Spivak. In the end, finding these was a pleasant distraction from finishing a synthesis of this week's reading.

Kokapeli is the common name given by commodifiers to the humpbacked flute player of Hopi mythology. Sold as Kachina, but actually a very important fertility being he is very, very sacred to many pueblo people, but especially the Hopi, (Water's Book of the Hopi). He is a good example of the artistic theft of motif from native mystery that permeates southwest art. Sold as jewelry, doll, garden decoration, and so forth Kokapeli has generated impressive financial streams that flow directly into corporate pockets. A few Native artists have made money with Kokapeli, but the desecration of sacred motif is generally white. The Book of the Hopi was written by Frank Waters in 1963 in conjunction with Oswald (White Bear) Fredericks. It was an extremely popular ethnography, best seller, and still in print today. Kokapilau, the hump back flute player who later became Kokapeli, the stolen art motif, was one of many Hopi deities revealed in Water's book. The sixties generation revered the Book of the Hopi, and I myself took names for my five children from its glossary of Hopi language. The secretive ceremonial life of this ancient people became common knowledge. Was this right or wrong? The original work was given to the world amidst a firestorm of controversy. It was said that revealing the religion of the Hopi would lead to exactly the kind of theft that Kokapilau experienced. Others said that it would open up white society to respect the ways of "other" people. Indeed, it did both.

Coombes says that the theft of culture is incredibly selective(244). "To claim Native spiritual practices, and traditions of motif and design, as part of contemporary Culture--or in the name of one's personal history -- while bypassing the history of racism, institutional abuse, poverty, and alienation that enabled its incorporation" (into Culture) "is simply to repeat the process by which the painful realities of contemporary Native life are continually ignored by those who feel more comfortable claiming the artifacts they have left 'behind'. Once again the Romantic author claims the expressive power to represent cultural others in the name of a heritage universalized as Culture." I would argue that the big C Culture that absorbs the little c culture is unstopppable, always has been and always will be. Hybridity studies the slippage between the two and results in expansion, inclusion, and domination. In the past the Hopi lived out their lives in anonymity, their religion secure for thousands of years inside their Kivas. But eventually the impact of euro-colonialism opened the sipapu and their mysteries poured up and out like so much smoke, while the cameras and recorders poured down upon them like rain.

Today the Hopi are entangled in legal battles, very much interactive with the big C culture around them, and still very protective of the remaining secrets of their ancient religion. For example, an elder is assigned to each child in school to help instruct the children in the ethics and morality traditionally taught to the youth of the tribe. While learning their ABC's and arithmetic, a Hopi child also learns respect for their elders, for their language and customs, etc. Nevertheless, they will see Kokapeli exploited all around them.

What can we do to protect what is left of indigenous culture? What about hybrid indigenous metaculture? Are we part of the colonial institution whether we like it or not? Can any white individual male priviledge (WIMP) person authentically address indigenous issues?

In The Cultural Life of Intellectual Properties: Authorship, Approbation, and the Law (1998) Rosemary Coombe draws on ethnography, anthropology, and cultural theory to forge a “critical cultural studies of law.” Examining “struggles around cultural forms” is crucial, she asserts, because the cultural dimensions and the political implications of intellectual property law have gone largely ignored in the scholarly literature (p. 7). In the many examples she considers where intellectual property disputes are sites of contested culture and identity, she highlights how certain groups invested with IP rights, such as corporations, have a monopoly over the meaning of certain signifying forms that they “own” (such as trademarks).

Coombe’s analysis of the cultural politics of trademark law leads to three major observations:

[1] The cultural politics of recoding commodified cultural forms—arts of approbation, recodings of trademarks, detournements of advertising texts, and improvisations upon the celebrity image—are neither readily appreciated using current juridical concepts nor easily encompassed by the liberal promises that ground our legal categories.

[2] Nor, within this Enlightenment framework, may the aspirations of indigenous peoples to protect the cultural indicia of the heritage and the harms experienced by virtue of the circulation of stereotypical representations be adequately acknowledged.

[3] The nexus of these difficulties may be located at the heart of the liberal legal discourse itself, its contradictions, instabilities, and ambiguities—aporias ever more apparent in late twentieth-century conditions. (p. 248)

Like Boyle, Coombe doesn’t simply advocate for either more or less restrictions on intellectual property rights. Rather, she argues that we need to revise our legal categories in ways that acknowledge trademarks and other signifiers as sites of identity negotiation. Coombe’s book is different from Boyle’s not only in its ethnographic approach to IP and the scholarly conversations she situates her critique within, but also in her emphasis on free speech in her recommendations for change.

I’d like to focus on free speech because it is what I see as ultimately at stake in a “critical cultural study of law.” Plus I hope to connect issues of free speech back up with Annita’s question in her post below on Chief Keef and respectful use.

In pointing to the trend of white consumers’ ironic covers of “ghetto rap,” Annita asks:

Aside from interrogating deep-seated racism and classism in order to treat rappers as artists and black people as human (something both monied suburban whites and the US government seem to be continuing to struggle with), what could an alternate nexus of copyright law/understanding of authorship, that is mindful of these kinds of pitfalls, look like?

My first reaction to Annita’s question was “yes, clearly these are examples of disrespectful use. But wouldn’t any legal policing of such use be easily blocked by appeals to the first amendment? Wouldn’t we have to speak out against these racist and classist approbations through non-legal means?”

But after reading Coombe I think there is a way to negotiate issues of respectful use in legal contexts. Coombe speaks directly to the issue of free speech/freedom of expression in her final two chapters on “Dialogic Democracy.” She points to the ways in which the Enlightenment understanding of free speech equates liberty with freedom from government intervention (258-9). This Enlightenment understanding is no longer relevant in a postmodern society where governmental regulation of media is necessary for ensuring a democratic political system. While the traditional, dominant conception of free speech operates through the Enlightenment dichotomies of public/private and citizen/state, a postmodern understanding of free speech would emphasize social context and dialogue:

A dialogic theory of human social life provides a means to reconceptualize and reorient the law of free speech or freedom of expression so that it focuses more on the conditions of interaction than on the interacting individuals—freedom not as a lack of all constraints but as an ability to participate in engaged conversations. The autonomy of the speaker from all social constraint is seen as illusory, because social situatedness is the very precondition for human speech. Instead, the conditions for maximum participation of all people in the ongoing negotiation of the social good must be promoted. (p. 266)

So yes, I think that we can make room for a consideration of “respectful use” in the legal system, but that task would require us to reframe the dominant conception of free speech. Free speech as Coombe imagines it could be would not just involve protecting an individual’s right to say anything, but would involve the consideration of how “speaking” is social event that takes place in a specific context. In emphasizing social contexts and the greater social good, the law would be positioned to recognize, for instance, how white covers of hip hop songs like the one Annita posted are situated within a long history of systematic white approbation of black cultural products and expressions.

Discussion questions:

1. To extend Annita’s original question, what might a legal enforcement of “respectful use” look like in regards to the example of the white covers of "ghetto rap" songs? In regards to Coombe's example of Crazy Horse malt liquor? In what ways, if any, would "respectful use" have to differentiate itself from “fair use”?

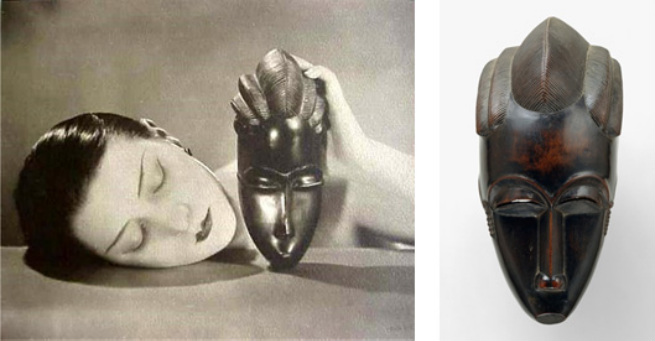

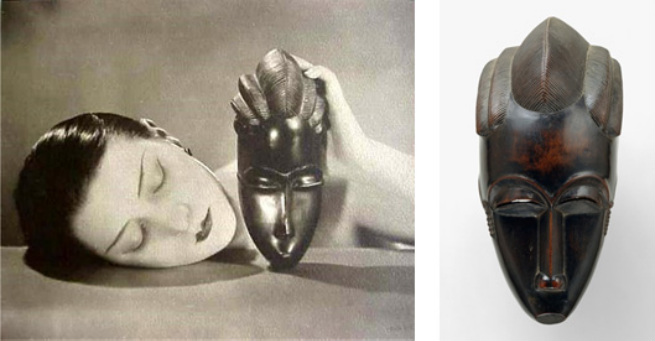

Left: Black and White, Man Ray, 1926. Right: Portrait Mask (Gba gba), Côte d'Ivoire, Baule peoples, before 1913. 2. In chapter five Coombe spends some time examining the categories of “authentic artifact” and “authentic masterpiece” that are at play in the European Art system. She specifically mentions the 1984 MOMA exhibition Primitivism in 20th Century Art (p. 217). As someone who has seen exhibitions on similar themes (how “primitive” or “oriental” art has influenced Man Ray, Monet, Picasso, Van Gogh, etc), I wonder how these exhibits might have been redone to foreground the “particular histories, local contexts, indigenous meanings, and the very political conditions that enabled Western artists and authors to seize these goods for their own ends” rather than just reproducing the image of indigenous art as decontextualized “artifacts” or “sources” for Western creation. How might the exhibition space be organized to open up the possibility of a historical and political analysis of this intertextuality? How might the exhibition work against the binary of “authentic masterpiece” and “authentic artifact”?

I didn't want to derail Tiffany's post re: Glee's cover of Sir Mix-a-Lot's Baby Got Back so I figured I'd just start a new post, because I really would like to have a conversation on cultural appropriation & hip hop (particularly trap/ghetto/gangster/whatever else white people call "non-conscious" rap genres).

Last week we talked about being mindful of boundaries and respectful use of indigenous knowledges and cultural practices--it's easy to preach that when we're talking about hypothetical Amazonian herbs, but how does that dialogue change when we're talking about something as easily consumable as a youtube video? Tiffany's post reminded me of the really problematic ways dominant narratives on both cultural appropriation and on respectful use are polarized to the benefit of those in privilege (particularly along axes of race & class)...the question I raised in my comment on her post is, why is no one asking what Sir Mix-a-Lot thinks of all this? I think this question can be expanded to open up a conversation on respectful use & hip hop more generally, and the ways in which copyright law as well as the dominant understanding of authorship in the US are lacking in ways that are especially detrimental to low-income communities of color.

I wanna present a mini genealogy of some of Chicago-based newly popular rapper Chief Keef's tracks as an example; we'll start with his breakout track, I Don't Like (please note the youtube video is heavily censored): I Don't Like earned Chief Keef rapid fame, & was later picked up & remixed by fellow Chicago rapper Kanye West, for his record label GOOD Music's newest compilation album, Cruel Summer. Chief Keef was featured on the track, alongside Pusha-T, Jadakiss, & Big Sean. While the track itself was a success and is immensely popular (and was produced with Chief Keef's involvement), some have criticized Kanye for essentially piggybacking on Chief Keef's aesthetic: Meanwhile, one of Chief Keef's other tracks, Love Sosa (along with the rest of his debut album) started to blow up and gain a wider audience. Thanks to "geek rockstars" like Coulton & Ben Folds' efforts to put ironic white acoustic covers of 'ghetto rap' on the map (note that the original artists, often POC from low-income areas like Dre, Sir Mix-a-Lot, & now Chief Keef are typically consumed by white audiences as dehumanized criminal thugs, while aforementioned white artists copping their experiences, aesthetics, & work are praised as comedic geniuses and rockstars), youtube is now chock full of annoying upper-middle class suburban white people doing acoustic covers of rap songs, like this one of Love Sosa: Technically, this girl's cover is legal because under copyright law it would be considered a derivative work (same as Coulton's cover of Baby Got Back); that said, it's incredibly offensive (and imo pathetic and boring in typical suburban saltine fashion). So how is it this girl has received tons of praise for this video, and this kind of appropriation is more popular than ever? When it comes down to it, respectful use is not something many white consumers of hip hop consider when appropriating/utilizing elements of hip hop culture(s) because the dominant landscape re: hip hop consumption (I'm talking about both copyright law and hegemonic cultural morays) simply does not require respect of black artists, and especially of uniquely black experiences and cultural expressions. Aside from interrogating deep-seated racism and classism in order to treat rappers as artists and black people as human (something both monied suburban whites and the US government seem to be continuing to struggle with), what could an alternate nexus of copyright law/understanding of authorship, that is mindful of these kinds of pitfalls, look like?

So, this was a post I meant to do days ago, but of course Life happened. Anyway, in an effort to mitigate my general lack of eloquence in class, I'm hoping to get more on this blogging scene. :)

First, let me just say that I am fascinated by YouTube, both as a collection of folk communities and as a virtual space fraught with anxiety about these very IP issues that we talk about in class. The IP issues are multi-layered; not only do users have to work around YouTube's increasingly strict rules about what can/cannot be posted on the site because of copyright reasons (more on that in a sec), but users also need to be aware of the rampant plagiarism amongst the users themselves. We see it all the time: someone posts something on YouTube, the video is downloaded (through easily available free software available elsewhere online), remixed in some fashion (or not, just reposted as "original"), and reuploaded to YouTube. The Sweet Brown viral video is just one recent example.

The complications here could be profound in terms of profiting from both the spread of the original as well as this and numerous other remixes. First, who uploaded the video originally? With some of these, it's impossible to tell. If someone uploads a video and says s/he is the original uploader and then monetizes that video (i.e. allows YouTube to place ads before or within the video, how often can it be proved that that is the original? And then someone is profiting from this woman's story, but I can pretty much guarantee that it's not her. Same with the remixes. Is that fair? Or did she give up rights by allowing herself to be interviewed by a television station in the first place? It's mind boggling. I've been through my own runarounds with YouTube in terms of posting original songs on the site, where I've had to prove without a doubt that I am the sole creator of said songs. In some cases, even notification by the software company that I use to create music on the computer that all of their samples are freely available for use and commercial rights got a big ol' HELL NO from YouTube. Thus I could not make a profit from views of certain videos even though the music was put together by me. For the corporate YouTube, of course, it only matters when they become potentially liable for copyright abuse; thus, they become so strict that a vlogger, for example, can't even have background music in her video when's it's playing on a car radio or a TV, for example. But all of this is leading me to the main event. Last week or so, I got a message from a YouTube user that I thought was a bit strange. He had apparently found one of my vlogs and was interesting in using the images for a music video of HIS original music. What I thought was strange was not that he wanted to use the images but that he actually contacted me to do so. He wanted to know whether the video was copyrighted. I told him it was, but if he credited me with the images and didn't monetize the video, then he could use my film.What came out of that is below (his music, my images). As it happens, the other user is from Italy, and he was as good as his word (the link to my original vlog is in his "about" section). But as this was going on, it made me wonder just how many times pieces of some random schmo's video (like me) get repurposed without the original user ever even knowing about it. And if the original user doesn't know it's going on, YouTube certainly doesn't have the resources to police that kind of thing. It rather reminds me of the tree in the forest question: if people don't know it's happening to them, is it really a problem? Just thinkin'.

I'm just putting this up on the blog for reference as one of any number of similar IP problems that crop up all the time. Apparently, the show Glee on Fox has recorded a Jonathan Coulton cover of Sir MixaLot's "Baby Got Back" and is selling the song on iTunes. The ensuing kerfuffle has brought up the issue of Creative Commons and what, exactly, is a do and a don't in that arena. Coulton, of course, fully acknowledges that the song is a cover, but his contribution to the song includes a "distinctive tune," new orchestration, and some changed words (not too many). The Glee version uses that same tune and orchestration. By many people's shorthand view of copyright, it seems obvious that Glee (ultimately Fox) is doing something "wrong" here because the orchestration is so close to Coulton's that the artist even speculates that they just took his actual recording and and put the cast's voices over it. And it may well be (I've only listened to the two versions once, but it sure sounds like that's the case). But it brings up so many cases that don't seem so obvious and forces us to ask, "Where do we draw that line?" Or, even, "Why should we draw a line?" It comes back to both the capitalist version of information production (who profits from the production and transmission of this information?) and the romantic author (it's MY orchestration). This isn't really super insightful or anything. These discussions just make me think of the classical European artists of earlier centuries where this wasn't even an issue. Heck, Handel was well known for reworking his own material, not to mention how others of those artists "plagiarized" (some might say borrowed from or were inspired by) each other's work.

(Post by Jen) While I was reading chapter two of The Cultural Life of Intellectual Properties last night I came across the passage where Coombe discusses "artists of approbation" like Cindy Sherman (p. 73). I thought immediately of the work of Candice Breitz, who creates art-space exhibits of fans performing their favorite albums. She has done exhibits on Michael Jackson, John Lennon, and Bob Marley. For each piece, she records about thirty fans singing/performing a particular album in its entirety and then plays these recordings simultaneously in the exhibition space, eliminating the original recording and music to leave just the voice and image of the fans. I read Breitz' work as an effort to make the discursive process of cultural production visible. In removing the original recording, she places emphasis on the fans, thus disrupting the dichotomy between subject and object. She shows how fans do not simply consume culture; they play an active role in its production and the negotiation of its meaning. In this sense, Bretitz' work reminds me of Bakhtin's concept of dialogics (Coombe, p. 82-3). Here is an article where you can read more about one of Bretiz' exhibits. This analysis of her work in particular caught my eye: Breitz is interested in the biographical aspect of pop culture, the way music and films become personal soundtracks to our lives. For her, and for so many of her contemporaries, using preexisting material from the mass media in order to create art is urgent, necessary, and practically unavoidable—a condition that mirrors the way commercial entertainment infiltrates all of our lives. Breitz's art reminds us of how important it is to step out of the role of passive consumer and digest mainstream media to our own ends. --Rudolf Frieling, SFMOMA Curator of Media Arts

Notice here how Frieling appeals to the rhetoric of "information wants to be free" when he states that "using preexisting material from the mass media in order to create art is urgent, necessary, and practically unavoidable." After reading Boyle, I can see how the assumption that appropriating preexisting materials is necessarily good (or even unavoidable) is problematic. It is interesting to see how the curator "sells" Breitz' work by appealing to this conception of information, even if I do not agree with his understanding of why her work is important in the first place.

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed