Indians in Unexpected Places by Philip J. Deloria is about rethinking “a particular history of expectation” in order to complicate and destabilize the often dangerous assumptions that Native peoples participated outside notions of modernity. Deloria examines the “secret histories” of a number of Indian people in the late 19th and early 20th century, who he conceptualizes as a cross-tribal cohort, to illustrate the complex relationship “Native life” had in “escaping familiar expectations and reinforcing them” (233). Deloria is interested in the imaginative process that shapes the way “expectations” get framed by non-Indians, such as the “native ability to commit violence.” The state, as we saw Deloria explain, justified violent repression against Natives in the name of self-defense by imagining Natives as savages, primitive and “un-civilized” (colonial language). However, Deloria is interested in deconstructing those expectations by putting them into dialogue with “unexpected” lived experiences of certain Native people in order to show why “certain kinds of telling [get told] and not others” (7). He centers stereotypes, discourse and ideology in his analysis to complicate the relationship between Indian people and the United States (11).

What stood out to me about the power of expectations is that Native people are always forced to confront these expectations; however confronting these colonial white expectations will be different based on one’s own social locality. Deloria wants us to think about how Native cultural productions of knowledge, and the actors of those productions, are embedded in a contradictory relationship with colonial white expectations, “usually challenging and reaffirming those expectations at the same time” (13). This was essential to my understanding of the text because Deloria is not interested in reproducing dichotomies or tracing how counter-hegemony operated within the realm of hegemonic discourses of power. I believe he sees micro-resistances and reaffirmations of expectations (that often occur simultaneously) not so much as products of a grand counter-hegemonic movement, but instead specific to the experiences of certain subjects, which he argues can help us see and challenge how colonial violence gets framed and why it gets framed that way, in addition to what stories get told and why those get told and not others. Deloria unveils “secret” histories with the political intention of making us rethink how we see history, more specifically, what stories do we decide to pay close attention to and which ones we choose to ignore, but more importantly how our own socialized “expectations” of Indigenity and modernity influence those decisions.

Questions:

Who is the intended audience in this text? Are there multiple audiences? Why is identifying the audience important for this text? Or is it important at all? Does having a specific audience take away or add to the book?

How can we use Deloria's framework for our own projects?

Deloria's text also made me think about other contemporary "expectations" of today's Natives, including the supposed "traditional knowledge" they keep about the future (or end) of the world. Mayans, Hopi -- there is a strong connection for some folks between some indigenous cultures in the Americas (can't speak about other places) and aliens, making Natives a solid part of UFO culture and lore. Of course, this is very much based on stereotypical views of Natives, but I am less interested in those stereotypes than in how they form a relationship with ideas about aliens and/or the apocalypse. -- Tiffany

Yeah, posting in pieces because that's how I process. Anyway, I started wondering why people who believe in aliens or apocalypse even need Indians mixed in there. I mean, beliefs in extraterrestrial beings and the end of the world have been around for centuries, certainly before the "New World" was "discovered." So what do indigenous groups from the Americas bring to the table?

In short? Authenticity. If one surmises (as some folklore researchers do) that aliens represent a secularized version of angels and demons, then Natives provide a link between the extraterrestrial (with their almost magical superior technology, not to mention being from realms unknown) and the terrestrial. If aliens have been around since the so-called ancient times, then only those peoples with ancient memories can attest to their reality with any surety. And Natives are perceived to have maintained an unbroken link to their ancestral heritage, including being able to translate petroglyphs that seem to show people meeting with alien beings.

With regard to the endtimes, the nature of the apocalypse in North America has also become increasingly secularized. Though there are still plenty of people who stick to Judgment Day according to the Book of Revelation, many people consider a more nature-alized scenario, where natural (or, again, extraterrestrial) disaster will wipe out great swaths of humanity.

Once again, with the general "expectation" that Natives have a stronger connection to the natural world than anyone else, a prophecy that predicts any major world change (often turned into an end of days scenario) provides authenticity. It absolutely does not matter whether such prophecies are "true" or "false," "real" or "not real." What matters is the affective relationship non-Natives have with their expectations of Natives in order to provide validity to apocalyptic scenarios or to visitations by alien beings.

(sorry for the book....had to get it out while I was still thinking about it.)

Philip J. Deloria’s Indians in unexpected places challenges readers not so much to ‘expect the unexpected’, but rather, to reconsider how and why expectations are the root of the problem to begin with. Deloria asserts: “As consumers of global mass-mediated culture, we are all subject to expectations. They sneak into our minds and down to our hearts when we aren’t looking. That does not mean, however, that they need to rule our thoughts” (6). From here, Deloria invites readers, through multi-layered “secret” narratives, to acknowledge the ways western conceptualized iteration of time and historical proofs continue to maintain First Peoples within stereotypical expectations. Launching his series of essays with a 1941 photo of “Red Cloud Woman in Beauty Shop, Denver 1941” where he interrogates the relationship between stereotype, ideology, and discourse. Deloria explains that expectation should be viewed as “a shorthand for the dense economies of meaning, representation, and act” that has held sway over American minds—Indian and non-Indian alike.

Indians in unexpected places is a series of compiled essays that seeks to (re) describe the stereotypical conceptions commonly held about First People. These essays range from the dual-representation of Indians as violent/pacifist to the careers Indians had in the nascent American sport industry to the juxtaposition of Indians and technology such as the automobile. Of particular intrigue for me was Deloria’s narration of his grandfather. Recounting the story of Vine Deloria Sr. ascendency as an Episcopalian minister, beloved by South Dakota congregations, Deloria situates his grandfather in the pivotal paradigm shift between savagery and pacification, belonging “to that ‘pacified’ generation of Native people who were supposed, once and for all, to be finally assimilating into the American melting pot or simply dying off” (112). Tracing Vine Deloria’s career as a football player, Deloria positions the rise of American consumer sports with that of marginalized bodies. However, as Deloria—as well as Tsing and Paige have—describes:

This new kind of athletic competition could sometimes be seen as part of a refigured warrior tradition, but it also provided an entrée into American society—a chance to beat whites at their own games, an opportunity to get an education, and, even at its most serious, an occasion for fun and sociality. (116)

Indians in unexpected places was a very interesting read, and has given me a much fuller comprehension not only in demystifying imaginaries of western linearity; but more importantly, how to possibly go about teaching First People history in the upcoming semesters to follow as an instructor in comparative ethnic studies.

Discussion Questions:

1 – One of Deloria’s main contentions is to address how Indian history has been documented and disseminated. As a critic to the hegemonic framework that attempts to make "sense of the diverse experiences of hundreds of tribal peoples" (11), Deloria concludes that this framework then becomes a narrative of U.S. government policy. What are your thoughts on this? I wonder if we can ascertain Deloria’s critique—that teaching First People history often becomes teaching about colonial rule—within the same lens that Coombe offers in her notion of cultural appropriation? What has been your relationship with institutional departments such as Ethnic Studies? Did you find it perpetuates or remedies Deloria’s argument?

2 – Describing that while the Indian athlete was granted access to the nascent U.S. sports economy, at the same time, Black and Latino bodies remained subjugated to institutional discrimination (125). Do you see any parallels in today’s contemporary capitalist moment? Has the era of appropriating marked bodies for specific purposes—or rather expectations—simply redesigned itself to include Black and Latino bodies now?

Philip J. Deloria’s Indians In Unexpected Places (2004) challenges non-Native readers in particular to rethink how they conceive of Natives as something dichotomous to "modern" space. He uses various examples from the beginning decades of the twentieth century (focusing on indigenous groups from the northern plains) to show how "a significant cohort of Native people engaged the same forces of modernization that were making non-Indians reevaluate their own expectations of themselves and their society" (6). Delving into the relationships Natives had with cars, sports, movies, and art song, Deloria tries to show how Natives taking part in these so-called modern activities, for whatever reason, went against non-Natives' expectations and thus worked to disrupt those expectations to varying extents.

As I read this text, I found myself speculating not only on the historical content but also on my own relationship to this book. It seems important not only to speculate on how "Indians in unexpected places" shaped non-Native views about Natives during this period in American history, but also to consider how those expectations continue to shape non-Native thought today. For example, the discussion of the singer Tsianina Redfeather in Chapter Five complicates the relationship between Native singers (in the context of "high" art song) and their white audiences. Deloria tells us that Tsianina Redfeather had to be seen as both authentically Indian and racially invisible in order to find a place of value on the stage, as her Indianness was mitigated by her talent as a vocalist. Thus, audiences could choose to focus on her race or deny it in favor of fixating on her talent, and somewhere in the gaps, there stood a Native singer participating in what is perceived of as a traditionally European musical realm. Standing squarely in that gap, these performers could "play…with white expectation, holding out familiar signs that proclaimed ‘Indian’ even as they offered more nuanced musical performances" (212).

My study of folklore has driven home the idea that tradition is dynamic, not static; the perception of the static-ness of tradition, however, gives it its value. In reading this chapter in particular, I found even myself momentarily surprised out of my own expectations of what constitutes traditional art song or opera (for which I, uh, thank a particular academic musical training), and I feel that this is exactly Deloria's point. While non-Native audiences of the time may or may not have been jarred out of their own expectations, the actual goal of this book is to jar us out of ours, either again or for the first time.

Apologies, but I'm having real issue in coming up with questions at the moment. TBD?

Deloria’s text Indians in Unexpected Places offers a detail-rich glimpse of the complex relationship Native Americans have with colonial notions of modernity and traditionalism, namely the massive divide between settler expectation and indigenous realities. While I admit that as a member of Native communities, many of the arguments voiced by Deloria, though compelling, seemed a bit self-evident to me—it seems clear that the target audience is primarily comprised of non-Natives, especially since I see the overarching take-away point to be that Natives are Actual Human Beings who don’t exist in an ahistorical essentialized cultural vacuum. That said, any glance at portrayals of Natives in dominant media is enough to prove that the text is a much-needed intervention. I do, moreover, appreciate Deloria’s dedication to complicating ideas of modernity altogether; rather than simply assert that Natives are modern too (and thus reify the modern/traditional bifurcation), Deloria demonstrates that Natives have played an active role in shaping modernity, and continue to construct paths around settler-imposed imaginations of traditionalism and Native culture while still maintaining identity as Native. In this way, he shows that the tired questions regarding “modernization” and its relation to alleged assimilation are not going to yield answers that speak to the myriad ways in which Native people have related to what is conceived of as modern. Again, this seems somewhat obvious to me, but Deloria does a great job showing the ways in which Northern Plains cultures are, contrary to settler thought, defined by ingenuity and innovation, and have routinely changed due to shifts in circumstance and preference. So what does this mean for Native cultures? Surely at the very least, that they’re emblematic of Native strength, resilience, and creativity. I recognize that for the purposes of this text, Deloria is much more concerned with how non-Natives are viewing and imagining Natives, rather than how Natives view their own cultures, but this has led me to wonder—is, to some degree, “modern-ness” traditional itself? If we understand Native traditions in their contexts (ie shaped by what was relevant and accessible to Native communities of the time), and are willing to concede that cultural traditions are fluid, wouldn’t this signify a total breakdown in the modern-traditional dichotomy, rather than a straddling of both sides? What is distinctly “un-modern” about practices that are now conceived of as traditional? Questions - How can Deloria’s arguments speak to or redefine our understandings of indigeneity? Of culture and modernity?

- How can we employ Deloria’s interventions in our understandings of (materials shown in class)? We’ve talked several times this semester about complications of a resistance-complicity dichotomy—how do you see this playing out in Native cultural practice, as seen in the examples either provided by Deloria or shown in class? How do Natives play with a modern-traditional dichotomy (that most understand as imagined) as a means of resistance?

- Do you see Deloria making larger interventions in landscapes of colonial imagination? If so, what do those look like? Again, we’ve talked several times this semester about the relationship between discursive space and material reality—if at face-value Deloria’s text is largely dealing with discursive intervention, how does it relate to past/present/future material realities for Native people?

In his 2004 book, Indians in Unexpected Places, Philip Deloria (2004) explored how imagery and stereotypes about Native Americans from a non-Native perspective is complicated by the persistence of Native people to exist and function in modernity. The title alludes to the fact that even today, non-Natives in the United States have specific expectations for how Native Americans should act, work and behave and that when Natives show up in unexpected places, like singing, driving or acting, this creates a discordance in the national narrative created about them. Throughout the essays comprised in this book, Deloria (2004) draws upon the framework of the non-Native’s history of expectation placed upon the Native Americans. Examining issues surrounding violence, masculinity, representation and technological modernity, to name a few, Deloria (2004) challenges the long held beliefs and stereotypes that have and still do subjugate and haunt Native Americans.

One aspect that I found particularly salient at this point in time was Deloria’s (2004) engagement with the technological. Specifically, he talked about the appropriation of Native names and terms for different car brands and models. This spoke to me on two levels: the first being that I am preparing a guest lecture for our Communication and Globalization undergraduate class tomorrow where I will be talking about Appadurai’s (1996) notion of the technoscape. Why this is relevant is that I am specifically going to be talking about not only the information technologies that have influenced global flows, but also the mechanical technologies. A question that we ask our undergraduates to get them thinking about technoscapes outside of the realm of the Internet and communication technologies is where their cars were made, with the follow up of: where was each part of your car made? This is when Deloria’s (2004) examination of technology and expectations hit me on a second level: When I was preparing tomorrow’s lecture, I thought about the car that I had when I was most of my students’ ages, and it was a Jeep Cherokee. That was my first car and while it was completely run-down, it was mostly reliable and perfect for growing up in Lake Tahoe. After reading Deloria (2004) however, I realized that I had never really given thought to the fact that I was driving a Cherokee (Native term) in Tahoe (Native land) and I think that the partial reason why is because of what Deloria (2004) meant when he said: “…there is a palpable disconnection between the high-tech automotive world and the primitivism that so often clings to the figure of the Indian” (p. 138). This more than anything else in his book framed one of his central theses best; which is that non-Natives often subconsciously place expectations upon Native people for how they should act, think and look-like. Looking back at my time with that 1987 Jeep Cherokee, I realize that we often take what we think are the “best parts” of a dominated culture—the name of a Nation for a car model, for example—and completely devalue the rest.

Questions for the Week:

1. Is this appropriation and expectation put upon Native Americans by non-Native similar to the kinds of appropriations and expectations we put on other dominated, minority groups (e.g., African Americans, queer individuals, etc.)?

2. How has this proliferation of specific expectations placed upon Native Americans by non-Natives influenced how other countries treat their indigenous populations?

References

Appadurai, A. (1996). Modernity at large: Cultural dimensions of globalization. Minneapolis, MN: University of

Minnesota Press.

Deloria, P. J. (2004). Indians in unexpected places. Lawrence, KS: University Press of Kansas.

Philip Deloria (2004) in Indians in Unexpected Places specifies that despite the passage of time, visions of

Native Americans within the dominant society remains locked up inside powerful stereotypes. He starts up with the description of a photograph of an Indian woman, dressed in a beaded buckskin dress, sitting under a salon hair dryer. He explains that the photograph not only juxtaposes whites' stereotype of Indians as rimitive and the technologies associated with modernity, but also reveals the colonial project. With this framework Deloria initiates discussions of how Native Americans often refuse to fulfill the expectations of non-Indians and established their own notion of Indianness that "engaged the same forces of modernization that were making non-Indians reevaluate their own expectation of themselves and their society" (p. 6). The book is focused on the late nineteenth and early twentieth century, when he claims America was going through the turmoil of anxieties regarding modernity and the coexistence with a large indigenous population. Throughout the book, Deloria investigates the artifacts of cultural production--Indian participation in athletic events, Indian purchases of automobiles, Indian performance in early film, and the adaptation of native music by whites. He particularly draws attention to the venues that are often overlooked by American Indian scholars as locations where Indians and non-Indians participate in a historical process that restructures the meaning and expectations of Indianness.

As I come from a communication background, I was particularly interested in the chapter about "Representation." Deloria examines the manifestation of Indian violence on the silver screen and investigates the participation of native actors in the construction of images that reinforce the image of a

historicized Indian. Deloria points out that while Indian actors fortified the stereotyped image of the violent Indian, they could also demonstrate to non-Indian audiences that Indians, as thespians, could participate in the modern world. However, non-Indians read Indian participation as a validation of misconstrued expectations, rather than evidence of Indian agency. This is because as Deloria specifies non-Indians closely linked authenticity and illusion, and for many "illusion came to matter more than authenticity" (p. 106). This revelation of agency construction by the Indians was particularly fascinating as it resonates with Tsing's (2005) concept of scales, how individuals construct agency using certain ideologies. The "Representation"

chapter I think provides a great example of the construction of Indian agency.

Further, in the "Representation" chapter, Deloria tells us that Indians protested the violent image of Indians in film when they viewed the pictures on reservations or while visiting larger cities. Deloria cites a southern Californian agent who said that Indians often spent their "last cent on a moving picture when they visited the city" (p. 92). Even though Deloria dissects the meaning of the image of Indians in the films, the role of the actors in reinforcing the expectations of non-Indians, and the protests of Indians against the images, I was wondering about the role of Indians as consumers of the cultural artifact. The early twentieth century marked a period where a growing consumer culture promised whites access to higher levels within a class hierarchy.

Therefore my questions:

1. Did non-Indian anxieties about Indian inclusion into American society prevent them from seeing native people as consumers in this example?

2. How did Indian people negotiate non-Indian expectations about consumerism?

References

Deloria, P. J. (2004).Indians in unexpected places. University Press of Kansas.

Tsing, A. L. (2005). Friction: An ethnography of global connection. Princeton University Press:

Princeton and Oxford.

Definitely the best book of the semester. Thoroughly enjoyed this scholarly look at expectations connected to Native Americans "assimilation" over the past two hundred years. As a guilty party to appropriating native primitiveness by living in a tipi in all weathers in Idaho, Oregon, and Washington I was especially moved by Phillip Deloria's exhaustive treatment of the ways Natives were and still are expected to act and be. I tried, along with many others of my generation of " white Americans sought reassurance: they might enjoy modernity while somehow escape its destructive consequences." In light of the foucoultian reservation surveillance system still in place, in spite of the hybridity of modern Indianness, and the self-determination policy finally bringing some sovereignty to the treatment of Native Americans in general, I feel this book should be required reading for every freshman university student. A student of American Indian history all my life I have immensely enjoyed the writings of the Delorias more than any other authors in the genre. So I am naturally thrilled to enter into a discussion with Deloria. Wow.

The past history of colonialism, assimilationism, and the present policy of self-determination examine the Native American story. Sadly it is a story of racism, eugenics, social evolution, and expectations based on racial stereotyping and generalizations. The opportunity to go ahead and be Indian in all its variety and expressions of sovereignty should be guaranteed to every American Indian person. The re-creation of the tribal circle is taking place on most reservations today (Harris, LaDonna, 2011) through self-determination of government, educational curriculae, economic development, and cultural revitalization, including language rejuvenation, ceremony, and spiritual renewal. My dissertation is on the return to Plateau reservations of Native American Students who have gone away to college with the idea of returning to help this process happen. With this new paradigm of multicultural hybridity, old ideas about assimilation into white mainstream culture are fading into the past, replaced by the self-determination trope. Government policy needs to continue changing in this direction to make the guarantee of Indianness real. Congress controls Indian affairs, and congress is still full of racist assimilationists, terminationists and white men like Senator Grassley, who oppose Indian sovereignty. Washington state has made huge strides toward self-determination of Indian tribes within its borders since the defeat of Slade Gorton by Maria Cantwell. The recent signing of the Violence Against Women Act (VAWA) by President Obama is another step forward for Indian sovereignty and the safety of Indian women. It finally makes it possible for tribal courts to prosecute white perpetrators of sexual violence against Native Women on reservations, something the FBI hardly ever did. Thousands of Native Women suffered such crimes at the hands of white men, including cops, over the years and watched their violators go free because the feds didn't think it was worth it to prosecute Indian Women's cases. After all, they are only Indians and only women. Most white american males are so blinded by their white male privileges as autonomous individuals they don't realize how racist their attitudes toward Indian women are. Hopefully VAWA will help change that attitude in America. Deloria's book handles such attitudes with dexterous aplomb. How much frontier tropes and early film had to do with incorporating Indian stereotyping into the consciousness of generations of white individual male privileged (WIMP's) is illustrated well by Deloria's treatment of the 1890-1920 period. That generation of racists influenced the war and depression generations of racists that influenced my generation. I thank God for the 1960's and the critical questioning that brought about the paradigm change of multiculturalism and the present self-determination policies. Native Americans would still be much worse off if it hadn't happened, along with African-Americans, Hispanics, and other people of color who have benefitted from the civil rights movement and lessening of racism. Still, so much work to do on that front. Hooray for Phillip Deloria's book. May it go viral in academic America. His theoretical basis in Foucault, Bhabha, Hall, Gramsci, Althusser, Said, Stoler, and others is academically above reproach, and his dedication to meticulous notation of his multiple sources outstanding. The indigenous people of the world are indebted to him for his accuracy in portraying how the American Indian has been involved in the creation of self-determination even though limited by colonialisms merciless applications. US history is more complete now, and American Indian history more real.

Questions: How does Deloria's book prompt one to feel about primitive stereotyping and racism today? Does it change perceptions of modernity, development, indigenousness, or

In Indians in Unexpected Places Philip Deloria challenges readers to rethink expectations of Native people and their engagement in modernization. Although he sets out to understand the relationship between Indians and non-Indians in broad terms, the five essays that make up the book’s chapters are focused both historically on the turn of the century and culturally on the Lakota, Dakota, and other Native people of the Northern plains. Deloria’s project to twofold: to expose and question a “history of expectation” and to examine the how these expectations came into being (p. 6-7). His definition of expectations is central to this project and bears repeating here:

When you encounter the word expectation in this book, I want you to read it as shorthand for the dense economies of meaning, representation, and act that have inflected both American culture writ large and individuals, both Indian and non-Indian. I would like for you to think of expectations in terms of the colonial and imperial relations of power and domination existing between Indian people and the United States. You might see in expectation the ways in which popular culture works to produce—and sometimes to compromise—racism and misogyny. And I would, finally, like you to distinguish between the anomalous, which reinforces expectations, and the unexpected, which resists categorization, and thereby, questions expectations itself. (p. 11)

Each of Deloria’s essay-chapters are dedicated to, as the book’s title suggests, exploring how Native people have engaged in modernization in unexpected ways (i.e ways that question expectations) in the early 20th century: through making and acting in films, shaping sports, owning cars, and creating music. Blending history and cultural analysis, Deloria ultimately calls into question the ways in which modernity has been imagined against and in opposition to Native “primitiveness.” At stake is our conception of modernity, and the expectations that carry through that imagined history into the present, expectations that reproduce “social, political, legal, and economic relations that are asymmetrical, sometimes grossly so” (p. 4).

One example of how Native people engaged actively in modernity came in the second essay on “representation.” Red Wing and Young Deer—film writers, directors, and actors—worked together on a series of movies that rejected the conventional depictions of Native peoples in film at the early 20th century (p. 94-103). Deloria compares how cross-racial relationships are represented in The Squaw Man compared to how they are represented in Red Wing and Young Deer’s The Falling Arrow. The plot of The Squaw Man was typical for the time: a white man saves and then marries an Indian woman (echoing the narrative of colonial conquest), who later kills herself so that the white man can be with a white woman (affirming white-on-white romance). The Falling Arrow inverses this conventional plot line: an Indian man saves a white woman from a white man, and then the white woman falls in love with the Indian man. This film’s plot line questioned the expectation that Indians to not have power over whites. Similarly, Red Wing and Young Deer’s status of film creators challenges the expectation that Native people are only represented in films as passive actors. Red Wing and Young Deer’s series of films demonstrates that Native people where actively involved in using the new technology of film to question the dominant representations of Native people at the time.

Discussion Questions:

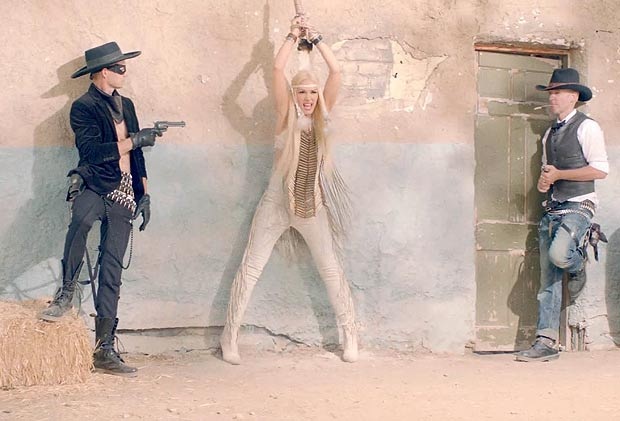

1. Some of you might have heard about this, but last fall No Doubt put out a music video that portrayed Gwen Stefani as an Indian woman. The band quickly took the video down from YouTube after coming under criticism from Native groups. (You can still find the video online against the band’s wishes, I think). What do you think Deloria would have to say about how the video engages expectations about Native people?

2. I think Deloria is strategically using what Tsing calls (ideological) scaling to make generalizable claims about the relationship between Indians and non-Indians. Since many of you will be using Tsing’s concept of scaling in your projects, do find Deloria’s strategic use of scaling to be effective?

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed