dovetailing off Deloria and Annita's thoughts in class. Check this out: on the politics of representation, the commodifying of stereotypical Indian-ness and the theoretical work the unexpected may do in undoing the desire to be a (part time) Indian.

Sorry everyone for being late with my post-discussion response! I’ll admit I think I needed a bit more time to collect my thoughts, and for the last 24 hours I’ve been stuck on a broke down bus in Montana and thus haven’t had internet access to upload this:

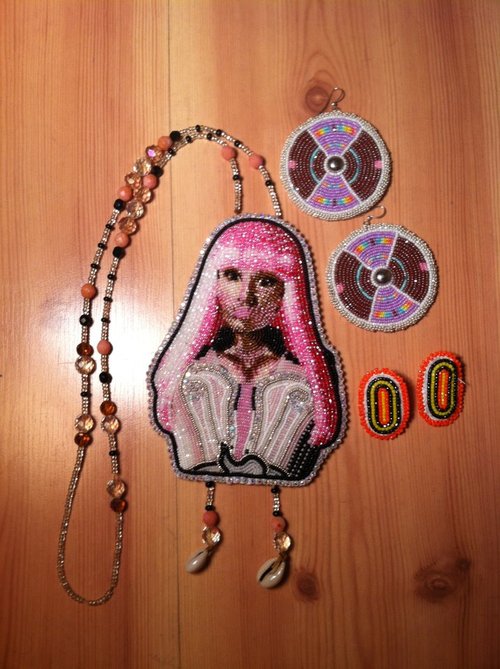

Most of my thoughts have been regarding why the conversation took the turns it did—I now realize that maybe some felt unprepared for the discussion I wanted to have due to a perceived ignorance re: “Native life,” or perhaps some apprehension related to uncomfortable confrontations of privilege. While to some degree I understand these sentiments, they make critical discussions of texts like Deloria’s all the more necessary. I urge anyone who may have felt this way to revisit the text, and to use this discomfort as a learning opportunity. Outside of those comments, I’m not sure that I have much to say that I haven’t said already, since I did most of the talking! Like I said earlier, I really value the text for its interventions re: troubling the modern-traditional dichotomy—in that vein, I’m still very much preoccupied with this notion of indigenous modernities, and what “modern-tradish” could signify. I have been thinking of it in relation to my project proposal at great length, since in many ways my work engages similar themes as raised by Deloria, and I feel the text can, in part, provide a strong theoretical foundation for my project. In particular I have been thinking on what the unexpected looks like within the context of indigenous modernities, especially as it relates to graffiti (something that very well fits within the parameters of the unexpected, yet, like so many of the examples discussed in class, is also tied to larger cultural traditions both in practice and theory). I’m not sure if I’ll ever get around to writing on this, but I think it also very closely ties into some of the larger Native conversations on indigenous fashion currently, which I am also very invested in. Is the beaded Nicki Minaj medallion below any less traditional than a beading pattern created 200 years ago? Is the style modeled by the designers behind the brand Indigenous Princess (also shown below) any less Tlingit than sealskin mukluks?  Today’s discussion of Deloria’s text was a tough one to process because of the complex ways we began to conceptualize modernity and traditionalism in relation to agency. Although Deloria is historically identifying the “unexpected” narratives of the 19th and 20th century, whihc allow us to see how Natives are indeed reaffirming, while simultaneously challenging white colonial expectations, he is also providing a theoretical framework that can be useful to contemporary discussions of Native agency in what I think Kim or Annita called a “playfulness of the settler’s imagination”. Annita aimed to take us there with her examples of anticolonial knowledge productions, but I think what happened in class today, yet I can only speak for myself, is that I got stuck in the modern and traditional, which unfortunately affected my inability to go to where Annita wanted us to go in terms of identifying these “unexpected” moments in contemporary productions of native agency as they complicate the boundaries of the modern and the traditional. Some of the questions that are still lingering in my head are questions that both Annita and Kim raised. They are: What does indigenous modernity look like and how are natives looking at those imaginative processes for their own political mobilization? And, do they (the Northern Cree and tribe called red) fit these unexpected frameworks or are they mainstreamed? These questions stood out to me because it complicates not only the way settler imagination creates expectations, but how Natives themselves are aware of those imaginative processes and often times they themselves use them, which goes back to this idea of “playfulness” that Annita or Kim raised, to mobilize their own agendas. Therefore to me, the modernity and traditional discussion was more about identifying how they do happen simultaneously and not in terms of dichotomy, which is why I think a lot of us in class had a difficult time grasping these concepts in the first place. I hope we can come back to this in class next week.

Have a good night y’all. While I remained slightly quieter than most weeks, I was very much working out the dialogue earlier today. For my post-discussion debrief, I would really like to talk about how I was dealing with some of the questions raised towards the end of class, particularly the notion of Indigenous Modernities.

I was having issues wrapping my head around the concepts of modernity vs. traditionalism. I understand the notion of modernity, as Jen shared, to be of ideological influence used in specific moments for specific reasons. This is wonderfully shown through Deloria’s diverse examples—via sports, automobiles, film representation etc and how he breaks dominant stereotypes that the Native body has always been in opposition to Modernity. Where I started having trouble keeping up was when the question of “what does indigenous modernity look like”? Below is the marathon that my frontal lobe ran while hearing y’all discuss: “Modernity is a concept that was/is used to legitimize and justify western ideology and practices in the Americas. Right? So if modernity is defined in accordance to the primitive—as West reminds us (frontiers of capitalism)—then the very concept of modernity lies in the separation from that which is not historically/distinctly white-capitalist? To situate Deloria’s theory of the unexpected, we can begin to understand how First Peoples have never been separated from the pathway toward modernity, but rather, the unexpected allows us to see the material realities of Modernity to be a fallacy in and of itself because Indians [have always been] in unexpected places. This makes the idea of indigenous modernities difficult for me to grasp seeing that modernity cannot identify itself without positioning itself in separation from an Othered. Does that make sense?” I guess what I am trying to express is that I cannot fathom right now as to whether Indigenous folks are/will be considered to be a part of Modernity if at the very seams these western stereotypes view Native peoples as anomalies to capitalism. Which is why, I believe, Deloria spent so much time excavating the 20th century’s then-contemporary capitalist moment (industrial capitalism). The capitalism of the 20th century is quite different from the capitalism of today. While the maintenance of a white-male only consumer was its priority, today (as we have seen through the interventions of Coombe and West) neoliberal capitalism functions by absorbing all/any difference. Annita’s examples of the musical works of Indigenous artists for me doesn’t suggest what Deloria calls “unexpected”—because I am viewing the “unexpected” to be situated in the way capitalism worked in the 20th century. So, given today’s neoliberal conjecture, I guess I ask are there really anymore “unexpected” examples today that cannot be consumed to be operative under Modernity (post-Modernity)? The Papua New Guinea folk surely give us some insight into this question right? Anyways, that is kinda what I have to share in this post-Deloria discussion brief. I apologize for submitting these thoughts later than intended, but this tofu lasagna took slightly longer to prepare/bake. Once again, it was a great pleasure to be a part of such a critical conversation. Hi All,

I think I am still as confused as I was in class and trying to collect my thoughts i think made it even more messy. But this is what my train of thoughts were, I think what I got from Deloria is the ongoing struggle between modernity and traditional. I think the reimagination of spatiality of the contexts with which engagement is essential is important but modernity narratives undermine it by treating it as a temporal process. I think what Deloria hinted was absent in the binary conception of modernity and traditional is the aspect of that the norm is attributing a singular universalizing concept of modernity and disregarding the possibility of more than one modernity. As Tsing had suggested, I think Deloria also implies that we need to look at modernity not only from the center to the periphery (indigenous culture), which is the norm in the modernity narratives but also how the periphery can diffuse to the center. For this reason, I think the question of "unexpected" rises. I think because the activity of the periphery in the creation of modernity remains systematically invisible at the center a narrative of traditional is imposed to channelize the process of diffusion only from center to periphery and not the other way round. Deloria explains in the final chapter how non-Indians translated the sounds of Native America into westernized music and used the recorded artifacts as the source for a new Americanized sound and also Annita's video both shows how the natives ridicule the non- native perception of Indians as primitive. Deloria examines both whites who chronicled Indian sounds and native performers who tried to bridge the world between Indianness and western music. He explores how Indians used non-Indian expectations alongside impressive talents associated with westernized music to draw white audiences. I think this successfully extends Deloria's questions about the historical construction of Indianness and expands a discussion raised by the author in the beginning of the book as he mentioned chuckles, as I stated in class also the Indians mimicking the expectations of non-Indians. Sorry if I sound confusing!!! Somava After today’s seminar talking about Deloria, I was actually really caught up in this notion of the traditional and the modern. I know that we talked about how the trajectory into the modern is not necessarily linear and that what non-Natives would see as “unexpected” or “anomalous” in the behaviors and/or actions of Native Americans is actually the result of our own inabilities to understand the evolution of specific tribes and Native nations. One aspect that really struck me was what Annita said when she was talking about the Plains Indians. To paraphrase, she said that the way they act today is, in essence, no different than the way they have conducted themselves for generations, it is just what is relevant to them now is different than what was relevant to them then. It was through this that I could start to better understand the layering of modern and traditional. This also made me think about how this notion could be applied to other communities who have been “stuck” in a particular set of expectations. As a member of the queer community, I was thinking about how the heterosexual majority has sort of “forced” us into the same notions of traditional without understanding how we can also live in the modern time without also wanting to completely assimilate into the “het culture.” I know this might not make a lot of sense (good to see I am still as confused/confusing as I was in class), but I was thinking about how divided the queer community is over the same sex marriage debate—some people see it as a logical right while others see it as trying to assimilate or “act straight.” After reading Deloria, I am starting to realize it might be something altogether different, something that cannot and should not be dictated by the discourses of the dominant groups in society. I am not sure this is making any sense, and it is making minimal sense in my head, but I am still grappling with the simultaneity of the modern and traditional. My fifteen minutes are up, and perhaps after some sleep some on this (even just a little bit) it might start making sense.

Philip Deloria mentions his grandfather throughout the book. An episcopalian minister, a rather unexpected vocational choice for a young man in his time. This brought to mind the influence of christianity as a social leveler. Missionaries get and deserved a bad rap for their racism and denial of religious freedom to the Indians in general, especially during the boarding school years. But many Christian Indians today are strong in their faith and religion is considered an important overall blessing in the lives of most reservations. Deloria writes with respect of his grandfather's life choice and I have interviewed Christian Indians of various denominations who say they are grateful for their christian experience. Just a thought. I think that Deloria made the point that racist expectations are misplaced. Natives involvement in many aspects of modernity portray clearly that the limitations racist views place on other than white races as primitive, incapable, lazy, etc. are just plain wrong and always have been. The colonial racism that caused so much death and hardship for Indians from the start of interracial contact is based on false assumptions of evolution and although Deloria never directly addressed it, the unexpected lives of his examples all have in common this thread, that other than white people are able to cope, survive, and civilize every bit as well as the descendants of Europeans, who were starving to death and living in utter squalor at the time of contact. For that matter, so able are the people of New Guinea, Indonesia, Africa, Brazil, Guatemala, etc. Today the inequality of globalization according to the neoliberal capitalist social development trope is reality. The recent indigenous social movement exhibited at Copenhagen where indigenous representatives from around the globe presented the bill for climate change to the rich nations illustrated clearly that reality. Reparations are called for, an end to racism is called for, indigenous rights are called for, and Deloria's work is part of that call.

Towards the end of class today we touched on the "work" of the narratives of modernity. I think Deloria would say that the narrative of modernity in the settler imagination is tied to a narrative of "primitiveness" or what we were calling in class the "traditional." Deloria suggests that these two narratives are co-dependent; modernity is constructed in opposition to the traditional. History with a capital H has often coded Native Indians as frozen in the traditional and non-Indians of the early twentieth century as moving towards modernity. Yet Deloria demonstrates that Native Indians have always been modern and have always participated in the shaping of modernity. As Annita pointed out in class (if I understand her correctly), Deloria implicitly critiques the linear trajectory that begins with the traditional and then moves towards the modern. This idea reminds me of West's critique of globalization as a linear process. (This critique is evoked in the title of her book, From Modern Production to Imagined Primitive.)

To return to Deloria, these narratives in the settler imagination and their relationship to one another are important because they continue to shape non-Indian expectations about Native Indian people. These expectations in turn create and reinforce systematic racism and material injustices. But the point that I was trying to get at in class but failed to articulate is that the "modern" as an ideological construct always functions historically and in specific geographical and cultural contexts. As such, the "modern" has not always been articulated by non-Indians as antithetical to primitiveness or to the traditional (I would contend that the "primitive" and the "traditional" are not always aligned in the settler imagination). On the contrary, early twentieth century non-Indians sometimes looked to and appropriated the "primitive" as a way of breaking away from a European past and carving out new paths towards modernity. While Picasso's use of African masks as models for his cubist paintings or Monet's use of Japanese prints as models for impressionism are clearly not American (but are easier for me to see at a distance precisely because they aren't American), I think that there is a similar approbation of the primitive in service of the modern in American contexts. I see this at work is just about every avant-garde modernist movement in American art and literature. I see it in the contradiction of giving cars (associated with the modern) Native Indian names (associated with the primitive). This is not to say that I am dismissing Deloria's main argument about the modern, the traditional, and how these shape expectations about Native Indians. On the contrary, I think Deloria's argument is real and important. However, Deloria's project is to understand the relationship between Indians and non-Indians in broad terms, to make generalizations. This aspect of his project is what I was trying to get at in my discussion question about strategic scaling. I just want to suggest that settler narratives of modernity and Native Indians are not always and everywhere the same, although they might nevertheless lead to expectations that contribute to similar forms of racism. Talking about the modern also made me think of Felski's "The Gender of Modernity," which I read back in my literature days. I think Felski's analysis of the connections between gender and modernity would enrich and bring nuance to Deloria's intervention. I've gone way over the 15 minute limit, so I am cutting myself off here. Post-Deloria, I'm thinking about why some people might be so hung up on needing a dichotomy between the traditional and the modern, and I remember something one of my mentors at U of O, Dr. Sharon Sherman, said. People often talk about traditions as being something "passed down" from one generation to the next as if they are these "pure," uncorruptable entities. But in the realm of folklore, the fact of variation -- whether "by accident" or by design -- puts in the forefront the idea that no tradition is "pure," that traditions are necessarily contingent. (After all of this, Dr. Sherman would always grunt disapprovingly when someone used the phrase "passed down.")

As I said in one of my previous posts and in class, the value of a tradition is in its perceived static-ness, and in its supposed purity. I kept thinking during class about Scottish kilts (A, because I love kilts, and B, because I'm not as up on Native cultures or "traditions" beyond what I've been fed through hegemonic discourse). Kilts in their present incarnation are something of an invented tradition (various stories about dressing up the basic tartan worn by people in the Highlands -- a garment that used to be loathed by those in the Lowlands -- circulate), now connected to Scottish nationalist history. Do the more constructed portions of the kilt's history mean it has less value, is less authentic? And, on another tack, could the kilt in 1782 be considered "traditional"? For Deloria's work (and others), I'm going to put myself out there and say that, among hegemonic discourse, there is a certain vested interest in maintaining a dichotomy between the traditional and the modern, both for Native histories and for the "American" story (sorry if I'm not wording that right...hopefully I'm making myself understood). Tradition implies an unbroken line to the past, and to admit to things such as invented traditions or tradition as a dynamic process -- again, either accidentally or deliberately so -- does mess with people's imagined ideas of what it means to "be" something. For hegemonic American culture, "tradition" is part of essentializing a Native identity, and there is a value that is attached to that identity (whether as the "noble savage" or as the "colonized heathen warrior" or some other stereotype). The value comes from the perceived purity of that identity as well as the production/creation of a line from the Native of today to some distant, imagined past. That value is disturbed when Deloria exposes the contingency of those traditions, showing that the creation of tradition is a modern activity and that the creation of modernity is a traditional activity. This, I think, ties in with Deloria's discussion of expectations as ideological constructs. Tradition, far from being "pure," is also an ideological construct, but to expose it as such has the effect, for some, of devaluing it. (This is not a comment on whether we should or should not work to expose traditions as constructed. Again, drawing from folklore, when I work with what is considered "traditional," I try to remember that said tradition is always contingent.) |

RSS Feed

RSS Feed