"The Right to Look: A Counterhistory of Visuality" by Nicholas Mirzoeff creates a "comparative decolonial framework for visual culture studies". Visualizing the enslaved, the oppressed, and the downtrodden Indigenous is countervisualization compared to the caesarian hero worship of warfare history I grew up with. Carlyle's history volumes are the thread throughout the book that the author uses to cast his fly onto the still waters of history and entice the big fish to strike, revealing racist colonialism in all its imperial splendor. The chapters on the demise of colonial slavery were especially interesting and, I think, authentic countervisualization, although they were not an exhaustive history and left out much detail. The end of slavery has been questioned recently by those who study today's slavery practices. Trafficing in slaves is apparently common with children and young women especially vulnerable in certain places around the globe.

Carlyle's hero worship was the way history was taught when I was in school. The evolutionary advance of civilization by war and invasion was enshrined in Alexander the Great, Julius Ceasar, and a long list of other conqueror/heroes produced by western civilization. Naturally, colonial visualization was a big part of the presentation of American exceptionalism. The revolutionary war heroics of George Washington, the civil war and the freeing of the slaves by Abraham Lincoln, these were the high points of history. No one brought up Europe and her colonies, other than to depose Monarchy and feudalism, so that America could prosper as the light of the civilized world. This look into truer history was both informative and timely. Countervisualization is an important text for American Studies to employ. Counterhistory critically encountered is always interesting, as we see different perspectives.

The Field Manual 3-24 of modern warfare acts as the endbooks for this counterhistorical escapade. CounterInsurgency (COIN) is now the worldwide battlefield that includes drone and cyber warfare, unlimited Presidential authority to wage endless war in preemptive strikes against enemies of US imperialism, economic hegemony, and cultural surveillance. The twenty-first century has already seen the destruction and occupation of ancient Babylon, which I participated in back in 2003, much to my chagrin. The RMA doctrine of the neoconservatives Rumsfeld, Wolfowitz, and Cheney pushed George W. Bush into regime change in Iraq. I was first sergeant of a National Guard Transportation unit called to active duty for the 2003 invasion. Being a National Guard Technician for 28 years, I was fully aware of what Bush was getting us into. My memories of the utter devastation squalor and poverty caused by the shock and awe campaign still visit my dreams 10 years later. The visualization I experienced there turned me against the war and caused my removal from my unit and eventual forced retirement for "medical" reasons. I guess you could say my countervisualization of the travesty I witnessed caused my separation from the virtual reality of the imagery presented to the public by the embedded media. I became an active member of Iraq Veterans Against the War and tried to activate WSU to no avail. The reasons for my failure to activate a countervisualization on campus should be obvious. The propaganda machinery brought to bear on public opinion overwhelmed the few opponents here. Anyway, General Betrayus got his way and we now have endless war, on the cyberbattlefield and video game representation of insurgency as terrorism.

Mirzoeff's book reveals the struggle against Euro-colonial slavery that took place in spite of the powerful monarchs of Europe and their naval power. The rebellion in Haiti, which is a stark contrast to Dominique next door today, especially since the earthquake, was visualized as a heroic Taussant leading a grassroots strike against the owners and overseers of the Island's cane plantations. The failure of the freedmen after the strike to create a sustainable economy of eating despite their claims to liberty and human rights raises the question of countervisualization's historical accuracy. The formation of Haiti resulted in a long disaster still unfolding. The counter history Haiti brings to the book is therefore problematic in that Haiti has not been a success since the revolt. Why not and what can be done now to help Haiti become sustainable?

Mirzoeff's "Right to Look: A Counterhistory of Visuality" explores the possibility that we are experiencing the unfolding of Orwellian surveillance, especially in the UK. Are we living "1984"? I think so.

The United State's political gridlock and the unlimited power of the Military Industrial Complex,(the wedding of private contractors with the Pentagon) feeds US Imperialism on the world wide battlefield. The everyday occurence of Drone strikes against human targets around the world and the collateral damage to innocent bystanders results in enhanced enmity against US Imperialism. Is this creating more enemies than it is destroying? I think so.

Final comment, Academia today is paying at least lip service to creating an interdisciplinary American Studies that conceives itself as critical cultural studies ranging from pop to hybridity. Does Mirzoeff's book represent a launching pad for countervisualization that will be useful in the future? I think so.

Nicholas Mirzoeff’s The Right to Look: A Counterhistory of Visuality (2011) presents a “decolonial genealogy” of visuality and countervisuality by exploring three “complexes of visuality” and their relationship to modernity (p. 8). Each of the chapters is dedicated to exploring these complexes in their “standard” and “intensified” forms, taking specific historical and geographical moments in each chapter as metonyms for larger social processes. Mirzeoff calls these three major complexes the plantation complex, the imperial complex, and the military-industrial complex.

Central to Mirzoeff’s project, then, is his distinction between visuality and claiming the right to look, or countervisuality. Visuality is the process of making authority “self-evident,” or normalizing hierarchies of power. Mirzoeff speaks of visuality as if it were itself a social agent: “visuality classifies by naming, categorizing, and defining […] visuality separates the groups so classified as a means of social organization […] it makes this separated classification seem right and hence aesthetic” (p. 3). The right to look, on the other hand, “claims autonomy from [the] authority [of visuality], refuses to be segregated, and spontaneously invents new forms” (p. 4). To provide a brief illustration of these terms per chapter five, visuality was at work when English missionaries sought to colonize the Maori of New Zealand. The missionaries sought to legitimize their power over Maori land, resources, and governing systems by claiming they were bringing “Christianity, commerce, and civilization” to the “blank spaces of the map” (p. 198-9). Papahurihia, a Maori religious leader, resisted colonial rule and claimed the right to look by forming an indigenous countervisuality. Paphurihia took the missionaries’ religious texts and used them to claim that the Maori were Jews, a claim that resulted in many Maori coming together in opposition to colonial rule.

As an academic speaking to other academics, Mirzoeff is concerned with the interpretation of authority and how this interpretation serves either neocolonial or decolonial ends. Ultimately, he argues that academics (and the government actors they influence) need to have more faith in countervisuality as a strategy for imagining and thus enacting a decolonial future. The pursuit of the right to look by thinking against visuality will result in the democratization of democracy: “the choice is between continuing to move on and authorizing authority or claiming there is something to see and democratizing democracy” (p. 5).

Discussion Questions

(A rough draft of my facilitation questions for chapters five and seven.)

1. Chapter five is titled “Imperial Visuality and Countervisuality, Ancient and Modern.” In this chapter, Mirzoeff looks at how the hierarchy that separated the “primitive” from the “civilized” played a central role in the imperial complex of visuality. He explains that imperial visuality

understood history to be arranged within and across time, meaning that the “civilized” were at the leading edge of time, while their “primitive” counterparts, although alive in the same moment, were understood as living in the past. This hierarchy ordered space and set boundaries to the limits of the possible, intending to make commerce the prime activity of humans within a sphere organized by Christianity and under the authority of civilization. Imperial visuality imagined a transhistorical genealogy of authority marked by a caesura of incommensurability between the “indigenous” and the “civilized,” whether that break had taken place in ancient Italy with the rise of the Romans, or was still being experienced, as in the colonial settlement of Pacific Island nations […] The classification of ancient and modern cultures, overlaid with that of the “primitive” and “civilized,” designated a separation in space and time that was aestheticized by European modernism. Despite the seemingly arbitrary nature of such formulae, the result was suturing of authority to the newly centralized modalities of imperial power. (p. 196-7)

What connections do you see in Mirzoeff’s exploration of the “primitive”/”civilized” hierarchy under imperial visuality and Deloria’s analysis of non-Indian expectations of the “modern” and the “indigenous”? What can Mirzoeff’s theories of visuality and countervisuality contribute to Deloria’s project of questioning the unexpected? How can Deloria expand or challenge your reading of Mirzoeff?

2. Chapter seven focuses on global counterinsurgency as the intensified form of the military-industrial complex. One tactic used in counterinsurgency efforts is the use of Unmanned Aerial Vehicles, or drones. The use of drones ties in to Mirzoeff’s discussion of necropolitics, deciding who should live and who should die. In this last presidential election, I was particularly disturbed by the invisibility—in the debates and in media coverage of the election—of drones and the Pakistan and Afghanistan civilians that the U.S. murdered with this technology. Is it accurate to characterize the use of drones as a colonial act? If so, what does the use of drones reveal about the role of technology in contemporary colonialism?

3. I’m really interested in Mirzoeff’s discussion of maps as tools for visuality or countervisuality. How might maps be used to claim the right to look in the current context of counterinsurgency?

4. In the last two pages of his book (p. 308-9), Mirzoeff asks if it is possible that “we construct a countervisuality to counterinsurgency.” He suggests that yes, academics in higher education can construct a countervisuality if they consider “combining democratization issues with education and sustainability in the institutions of education.” However, Mirzoeff does not provide us with specifics about how this might be accomplished. All of us in class teach in higher education. Assuming that you agree with Mirzoeff’s argument and call to action, in what ways could you participate in forming a collective countervisuality to counterinsurgency? What are some of the obstacles or challenges of reaching this goal? What might countervisuality look like and how do we move in that direction as teachers?

"Here one drowns/we drown Algerians"

I know that the reading for this week was dense and that we are only assigned the introduction and chapters 2, 5, and 7. However, I just want to encourage you to skim through chapter 6 which focuses on the Algerian War. In this chapter, Mirzoeff does a great job of analyzing the visual imagery in films about the Algerian War and connecting these analyses to his overall argument about visuality and countervisuality. I found the use of examples clearer than those in chapter 5. Reading through this chapter and make me think of the October 17, 1961 massacre of Algerian protesters in Paris. Although Mirzoeff does not mention this event in the chapter (unless I missed it), the massacre--which involved the violent murder of some 70-200 peaceful protesters by Paris police and the beating and arrest of hundreds of others, and for which the French government has yet to officially apologize--seems to me an illustration of visuality working to render the Other invisible.

"To the memory of the many Algerians killed during the bloody repression of the non-violent protest of October 17, 1961" | Walkway of Fraternity

dovetailing off Deloria and Annita's thoughts in class. Check this out: on the politics of representation, the commodifying of stereotypical Indian-ness and the theoretical work the unexpected may do in undoing the desire to be a (part time) Indian.

Sorry everyone for being late with my post-discussion response! I’ll admit I think I needed a bit more time to collect my thoughts, and for the last 24 hours I’ve been stuck on a broke down bus in Montana and thus haven’t had internet access to upload this:

Most of my thoughts have been regarding why the conversation took the turns it did—I now realize that maybe some felt unprepared for the discussion I wanted to have due to a perceived ignorance re: “Native life,” or perhaps some apprehension related to uncomfortable confrontations of privilege. While to some degree I understand these sentiments, they make critical discussions of texts like Deloria’s all the more necessary. I urge anyone who may have felt this way to revisit the text, and to use this discomfort as a learning opportunity.

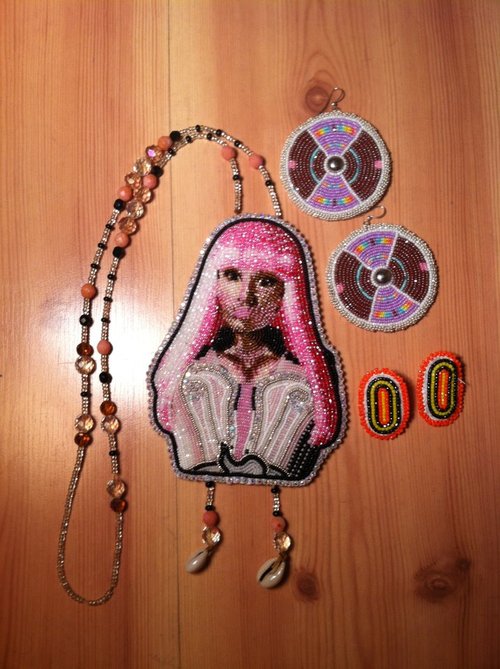

Outside of those comments, I’m not sure that I have much to say that I haven’t said already, since I did most of the talking! Like I said earlier, I really value the text for its interventions re: troubling the modern-traditional dichotomy—in that vein, I’m still very much preoccupied with this notion of indigenous modernities, and what “modern-tradish” could signify. I have been thinking of it in relation to my project proposal at great length, since in many ways my work engages similar themes as raised by Deloria, and I feel the text can, in part, provide a strong theoretical foundation for my project. In particular I have been thinking on what the unexpected looks like within the context of indigenous modernities, especially as it relates to graffiti (something that very well fits within the parameters of the unexpected, yet, like so many of the examples discussed in class, is also tied to larger cultural traditions both in practice and theory). I’m not sure if I’ll ever get around to writing on this, but I think it also very closely ties into some of the larger Native conversations on indigenous fashion currently, which I am also very invested in. Is the beaded Nicki Minaj medallion below any less traditional than a beading pattern created 200 years ago? Is the style modeled by the designers behind the brand Indigenous Princess (also shown below) any less Tlingit than sealskin mukluks?

Today’s discussion of Deloria’s text was a tough one to process because of the complex ways we began to conceptualize modernity and traditionalism in relation to agency. Although Deloria is historically identifying the “unexpected” narratives of the 19th and 20th century, whihc allow us to see how Natives are indeed reaffirming, while simultaneously challenging white colonial expectations, he is also providing a theoretical framework that can be useful to contemporary discussions of Native agency in what I think Kim or Annita called a “playfulness of the settler’s imagination”. Annita aimed to take us there with her examples of anticolonial knowledge productions, but I think what happened in class today, yet I can only speak for myself, is that I got stuck in the modern and traditional, which unfortunately affected my inability to go to where Annita wanted us to go in terms of identifying these “unexpected” moments in contemporary productions of native agency as they complicate the boundaries of the modern and the traditional. Some of the questions that are still lingering in my head are questions that both Annita and Kim raised. They are: What does indigenous modernity look like and how are natives looking at those imaginative processes for their own political mobilization? And, do they (the Northern Cree and tribe called red) fit these unexpected frameworks or are they mainstreamed? These questions stood out to me because it complicates not only the way settler imagination creates expectations, but how Natives themselves are aware of those imaginative processes and often times they themselves use them, which goes back to this idea of “playfulness” that Annita or Kim raised, to mobilize their own agendas. Therefore to me, the modernity and traditional discussion was more about identifying how they do happen simultaneously and not in terms of dichotomy, which is why I think a lot of us in class had a difficult time grasping these concepts in the first place. I hope we can come back to this in class next week.

Have a good night y’all.

While I remained slightly quieter than most weeks, I was very much working out the dialogue earlier today. For my post-discussion debrief, I would really like to talk about how I was dealing with some of the questions raised towards the end of class, particularly the notion of Indigenous Modernities.

I was having issues wrapping my head around the concepts of modernity vs. traditionalism. I understand the notion of modernity, as Jen shared, to be of ideological influence used in specific moments for specific reasons. This is wonderfully shown through Deloria’s diverse examples—via sports, automobiles, film representation etc and how he breaks dominant stereotypes that the Native body has always been in opposition to Modernity. Where I started having trouble keeping up was when the question of “what does indigenous modernity look like”? Below is the marathon that my frontal lobe ran while hearing y’all discuss:

“Modernity is a concept that was/is used to legitimize and justify western ideology and practices in the Americas. Right? So if modernity is defined in accordance to the primitive—as West reminds us (frontiers of capitalism)—then the very concept of modernity lies in the separation from that which is not historically/distinctly white-capitalist?

To situate Deloria’s theory of the unexpected, we can begin to understand how First Peoples have never been separated from the pathway toward modernity, but rather, the unexpected allows us to see the material realities of Modernity to be a fallacy in and of itself because Indians [have always been] in unexpected places.

This makes the idea of indigenous modernities difficult for me to grasp seeing that modernity cannot identify itself without positioning itself in separation from an Othered. Does that make sense?”

I guess what I am trying to express is that I cannot fathom right now as to whether Indigenous folks are/will be considered to be a part of Modernity if at the very seams these western stereotypes view Native peoples as anomalies to capitalism. Which is why, I believe, Deloria spent so much time excavating the 20th century’s then-contemporary capitalist moment (industrial capitalism).

The capitalism of the 20th century is quite different from the capitalism of today. While the maintenance of a white-male only consumer was its priority, today (as we have seen through the interventions of Coombe and West) neoliberal capitalism functions by absorbing all/any difference.

Annita’s examples of the musical works of Indigenous artists for me doesn’t suggest what Deloria calls “unexpected”—because I am viewing the “unexpected” to be situated in the way capitalism worked in the 20th century. So, given today’s neoliberal conjecture, I guess I ask are there really anymore “unexpected” examples today that cannot be consumed to be operative under Modernity (post-Modernity)? The Papua New Guinea folk surely give us some insight into this question right?

Anyways, that is kinda what I have to share in this post-Deloria discussion brief. I apologize for submitting these thoughts later than intended, but this tofu lasagna took slightly longer to prepare/bake. Once again, it was a great pleasure to be a part of such a critical conversation.

Hi All,

I think I am still as confused as I was in class and trying to collect my thoughts i think made it even more messy. But this is what my train of thoughts were,

I think what I got from Deloria is the ongoing struggle between modernity and traditional. I think the reimagination of spatiality of the contexts with which engagement is essential is important but modernity narratives undermine it by treating it as a temporal process. I think what Deloria hinted was absent in

the binary conception of modernity and traditional is the aspect of that the norm is attributing a singular universalizing concept of modernity and disregarding the possibility of more than one modernity. As Tsing had suggested, I think Deloria also implies that we need to look at modernity not only from the center to the periphery (indigenous culture), which is the norm in the modernity narratives but also how the periphery can diffuse to the center. For this reason, I think the question of "unexpected" rises. I think because the

activity of the periphery in the creation of modernity remains systematically invisible at the center a narrative of traditional is imposed to channelize the process of diffusion only from center to periphery and not the other way round.

Deloria explains in the final chapter how non-Indians translated the sounds of Native America into westernized music and used the recorded artifacts as the source for a new Americanized sound and also Annita's video both shows how the natives ridicule the non- native perception of Indians as primitive. Deloria examines both whites who chronicled Indian sounds and native performers who tried to bridge the world between Indianness and western music. He explores how Indians used non-Indian expectations alongside impressive talents associated with westernized music to draw white audiences. I think this successfully extends Deloria's questions about the historical construction of Indianness and expands a discussion raised by the author in the beginning of the book as he mentioned chuckles, as I stated in class also the Indians mimicking the expectations of non-Indians.

Sorry if I sound confusing!!!

Somava

After today’s seminar talking about Deloria, I was actually really caught up in this notion of the traditional and the modern. I know that we talked about how the trajectory into the modern is not necessarily linear and that what non-Natives would see as “unexpected” or “anomalous” in the behaviors and/or actions of Native Americans is actually the result of our own inabilities to understand the evolution of specific tribes and Native nations. One aspect that really struck me was what Annita said when she was talking about the Plains Indians. To paraphrase, she said that the way they act today is, in essence, no different than the way they have conducted themselves for generations, it is just what is relevant to them now is different than what was relevant to them then. It was through this that I could start to better understand the layering of modern and traditional. This also made me think about how this notion could be applied to other communities who have been “stuck” in a particular set of expectations. As a member of the queer community, I was thinking about how the heterosexual majority has sort of “forced” us into the same notions of traditional without understanding how we can also live in the modern time without also wanting to completely assimilate into the “het culture.” I know this might not make a lot of sense (good to see I am still as confused/confusing as I was in class), but I was thinking about how divided the queer community is over the same sex marriage debate—some people see it as a logical right while others see it as trying to assimilate or “act straight.” After reading Deloria, I am starting to realize it might be something altogether different, something that cannot and should not be dictated by the discourses of the dominant groups in society. I am not sure this is making any sense, and it is making minimal sense in my head, but I am still grappling with the simultaneity of the modern and traditional. My fifteen minutes are up, and perhaps after some sleep some on this (even just a little bit) it might start making sense.

Philip Deloria mentions his grandfather throughout the book. An episcopalian minister, a rather unexpected vocational choice for a young man in his time. This brought to mind the influence of christianity as a social leveler. Missionaries get and deserved a bad rap for their racism and denial of religious freedom to the Indians in general, especially during the boarding school years. But many Christian Indians today are strong in their faith and religion is considered an important overall blessing in the lives of most reservations. Deloria writes with respect of his grandfather's life choice and I have interviewed Christian Indians of various denominations who say they are grateful for their christian experience. Just a thought. I think that Deloria made the point that racist expectations are misplaced. Natives involvement in many aspects of modernity portray clearly that the limitations racist views place on other than white races as primitive, incapable, lazy, etc. are just plain wrong and always have been. The colonial racism that caused so much death and hardship for Indians from the start of interracial contact is based on false assumptions of evolution and although Deloria never directly addressed it, the unexpected lives of his examples all have in common this thread, that other than white people are able to cope, survive, and civilize every bit as well as the descendants of Europeans, who were starving to death and living in utter squalor at the time of contact. For that matter, so able are the people of New Guinea, Indonesia, Africa, Brazil, Guatemala, etc. Today the inequality of globalization according to the neoliberal capitalist social development trope is reality. The recent indigenous social movement exhibited at Copenhagen where indigenous representatives from around the globe presented the bill for climate change to the rich nations illustrated clearly that reality. Reparations are called for, an end to racism is called for, indigenous rights are called for, and Deloria's work is part of that call.

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed