mural by Corey Bulpitt (Haida) Background: While considerable work has been done on graffiti and its role in renegotiating power dynamics in public spaces, particularly for low-income people of color, these conversations are primarily centered on urban African American and Latin@ experiences of marginalization and subsequent resistance. Native Americans are notably absent from this discourse, perhaps due to a presumption that they do not partake in cultural expressions long stereotyped as solely urban (and thus implicitly coded as unique to Black and Latin@ communities), or maybe even a total denial of the existence of urban Native communities entirely. Whatever the case, the absence of Natives from discourses on graffiti and renegotiations of public space is not reflective of actual landscapes of public resistance art. Both New York City and Los Angeles are home to more than 50,000 American Indians each, and the majority of American Indians now live in urban areas (other major cities include Seattle, San Francisco, Minneapolis, etc)—the last 50 years of forced relocation and urban migration have firmly placed Native peoples in urban spaces, and these urban Native communities have a long and vibrant history of graffiti as resistance. Moreover, graffiti is not limited to urban cityscapes, and indeed has become quite popular on reservations and in rural areas—in other words, the backwaters Native peoples are assumed to inhabit. There has been an increasing interest in graffiti as resistance strategy among urban and rural Natives alike, particularly in light of Idle No More, and typically the methodologies and aesthetics of this kind of work overtly engage themes of colonialism, territoriality, and indigeneity.

Questions:- How does Native graffiti work to interrogate colonial cartographies of territory?

- What kind of spaces do Native graffiti praxes weave together in their expressions of indigeneity and spatialized resistance?

- How can understanding Native graffiti as an anticolonial remapping technology aid in larger projects of decolonization?

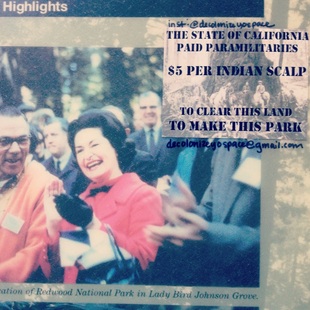

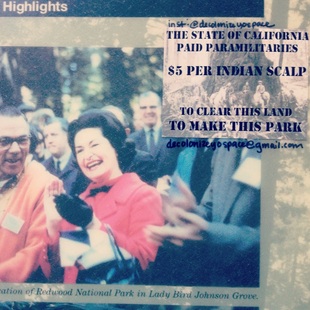

original photo; Ladybird Johnson Grove 2013 Methodology: This project is firmly rooted in a participatory praxis; as a Native graffiti artist myself, I believe my perspective and community memberships situate me in a unique vantage point from which to understand the questions outlined above. I intend to critically examine a broad survey of Native graffiti and public art across the US (see photo examples in post), studying the methodologies, aesthetics, and Native-led discourses associated with the selected works. Additionally, I will include an analysis of my own work in the medium thus far, and in this vein move forward with an ongoing project of mine as a means of continued exploration. This includes previous fieldwork conducted in Northern California, as well as in-progress work in Seattle and various areas of the Pacific Northwest.

original photo; Redwood Nat'l Park 2013 Arguments: I contend that graffiti and other forms of public art have offered Native peoples in both urban and rural locales means to renegotiate colonized public spaces. This kind of engagement with everyday landscapes of power works to redefine a mutually constitutive relationship with discursive spaces in which Native peoples are popularly understood as positioned as powerless and defeated—to the contrary, this reconfiguration of public space shows that Native peoples are continuing to engage in anticolonial struggle and maintain agency therein. Moreover, through this praxis Native artists are not only reworking their relationships to discursive-material landscapes of colonial power, but also forging a dynamic and culturally varied space for indigenous resistance that can move outside Western colonial impositions of nationality, boundaries, and territory.

Sources: The primary text I expect to be working with is Philip Deloria’s Indians in Unexpected Places, though I also see possible theoretical ties with Anna Tsing’s Friction: An Ethnography of Global Connection. I have a strong understanding of contemporary Native scholarly conversations on pan-Indian cartographies, questions of boundary drawing and nationality, as well as efforts to move outside of Western territorialities—I expect to draw on that to some degree, though I’ll admit a lot of my source material is original ethnography. In terms of Native scholarship, I draw considerable influence from Heidi Kiiwetinepinesiik, Brian Thom, and Taiaiake Alfred. To a much lesser degree, I may also build on some of the Gramsci readings from last semester.

JUSTIFICATION OF RESEARCH In Networks of Outrage and Hope, Castells’ (2012) examined the role of new communication technologies, like social networking, and their impact on social movements around the world. Outlining several different social and political movements from around the world, Castells (2012) explored what he calls “the new public space”—that “…networked space between the digital space and the urban space…” (p. 11) which he sees as a space of autonomous communication. This new public space is ground for the coalition of what Castells (2012) saw as networks of outrage and hope. As he conceptualized it, social movements are often born out of outrage: outrage at oppression and hegemony, personal rights violations and abuses. These movements are sustained through hope: hope that these movements can and will illicit social and political change. His research demonstrates how these new social movements fluidly move back and forth between the virtual and physical realms and that while much of the social and political change happens in the physical realm, movements are sustained, organized and given a global audience in the virtual realm.

It is with this in mind that I want to look at another sort of movement that has been occurring mostly in the virtual realm, with moments of uprising within the physical: the anti-bullying movement within the queer community as started by the “It Gets Better” campaign. It Gets Better was started by Dan Savage and his husband, Terry Miller. In September 2010, Savage, a journalist, and Miller, posted a video on YouTube in response to the recent spate of suicides amongst young people who had been bullied because of their presumed sexual and/or gender identity expression. Originally, the video was meant to be a “one-off,” a one-time posting that gave hope to young queer individuals who were facing harassment in their lives. The message was simple: please don’t kill yourself because it gets better. Within a week, the video went viral and soon more people were uploading videos to the official YouTube site with the same message: “It Gets Better.” To date, there are over 50,000 It Gets Better videos uploaded to the Internet, there have been MTV specials recorded, a book has been published, and there are grassroots campaigns across the globe that are trying to change policy within communities and societies to legislate against homophobic bullying (“It Gets Better,” 2013).

The “It Gets Better” movement, like the others that Castells’ (2012) examined, was born out of outrage: specifically Savage’s outrage at the seeming social apathy at homophobic bullying and suicides. Also, like the other movements examined by Castells (2012), this movement is sustained by hope: in this case, literal hope that if queer youth can just stay strong, it will eventually get better. While there has been vocal criticism of this approach, mostly that we as a society cannot really guarantee that it is going to get better for all queer youth, there is no denying that the movement has been a cultural zeitgeist and that there has indeed been change in states like Hawaii and Michigan, which have added anti-bullying statues and states like Massachusetts which have broadened already existing anti-bullying laws to include bullying based on sexual and/or gender identity expression (“Bully Police,” 2012). More importantly, however, is that the virtual network created by the It Gets Better campaign is giving life-sustaining hope to queer youth who are living in states where there is no legal protection against anti-gay bullying. This campaign, however, has not been a queer utopia of hope, and while it has been the subject of praise from the highest critics, it has also been subjected to some of the harshest critiques, especially within the queer community. It is because of this seeming contradiction that I am interested in studying the It Gets Better campaign as a new kind of social movement.

RESEARCH QUESTIONS One of the issues I am interested in examining in this project is what are the implications of a movement that does not seem to have a specific end goal in mind. The whole message of “it gets better,” while hopeful, is nebulous and often criticized for being too general. While there has been some actual policy change that has been created in light of the increased exposure to the systemic problem of queer bullying and suicides, there is no specific timeline or “set of specific demands” for society to change or adapt. In reality, the It Gets Better movement places a tremendous amount of onus on the individuals getting bullied, specifically that if it does not get better for them in the future, it must be something they are doing wrong. It is with this that I am interested in the following general research question: How successful is a movement like the “It Gets Better” campaign when there are no specific, legislative demands put on society at large?

Another issue that I am interested in for this project is the fact that most of the videos posted to the It Gets Better YouTube page are created by regular people throughout the world. While Savage and Miller created the first video, they do not purport to “own the idea” and encourage others to post videos and disseminate the information found in the videos. In this way, it echoes Coleman’s (2013) examination of creative commons and “copyleft” laws. Rather than trying to control the information and ideas expressed in the original It Gets Better video, Savage and Miller have opened it to the global virtual community. In essence, the It Gets Better campaign has done away with the idea of a romantic author within the project. My research question in regards to this line of thinking is how that has affected the credibility of the campaign—both amongst the people whom the videos are targeted at (queer youth) and policy makers at the political level.

METHODOLOGY The methodology I plan on using for this project is based upon Castells’ (2012) framework for examining the various social movements detailed within Networks of Outrage and Hope. Specifically, Castells’ (2012) stated that: “…my theory will be embedded in a selective observation of the movements, to bring together…the most salient findings of this study in an analytical framework” (p. 17-18). Similarly, I am going to selectively “observe” different aspects of the It Gets Better campaign within the framework of Appadurai’s (1990) “-scapes” of the social imaginary. Appadurai (1990), by way of Anderson’s (2006) Imagined Communities, has conceptualized of five different -scapes through with information and ideas flow within the global community. The five –scapes are: the ethnoscape, the technoscape, the finanscape, mediascape, and the ideoscape. While the It Gets Better relies heavily upon techno- and mediascapes, there is evidence of influence from all five of Appadurai’s (1990) –scapes. By using Appadurai’s (1990) social imaginary of –scapes through the selective observation of the It Gets Better campaign and subsequent movement, I hope to answer the research questions outlined above.

ARGUMENT/HYPOTHESES I believe that while the It Gets Better campaign has created hope and change in the lives of millions of young queer individuals across the globe, because it is a movement that exists almost completely within the virtual realm, it does not have nearly as much tangible social change as the movements that were analyzed by Castells (2012). The fact that much of the movement is online is of specific interest to me, especially in regards to Hall’s (1996) notions of the displacements of centered discourses and how they apply to discourses within the virtual realm. Also, I believe that because the movement is not prescriptive, calling for specific actions by the government, but merely asking for queer youth to be patient until it gets better, the It Gets Better campaign acts as little more than just a global media event with moments mirroring a social movement. I am also, aware of the fact that perhaps the It Gets Better campaign is a new kind of movement, one that does not illicit relatively immediate change like movements within the Arab Spring did, but is a movement that will happen over the course of years or even decades when individuals who are raised on tolerance, acceptance and hope eventually take over the positions of power within the government and society.

INITIAL AUTHORS/REFERENCES Anderson, B. (2006). Imagined communities, new edition. London: Verso.

Appadurai, A. (1990). Disjuncture and difference in the global cultural economy. Theory, Culture & Society, 7, 295-310. doi: 10.1177/026327690007002017

Bully Police. (2012). Bully Police USA. Retrieved from http://www.bullypolice.org

Castells, M. (2012). Networks of outrage and hope: Social movements in the Internet age. Maiden, MA: Polity.

Coleman, E. G. (2013). Coding freedom: The ethics and aesthetics of hacking. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press.

Hall, S. (1996). New ethnicities. In D. Morley & K-. H. Chen (Eds.), Stuart Hall: Critical dialogues in cultural studies. London: Routledge.

It Gets Better. (2013). It Gets Better- About Page. Retrieved from http://www.itge

Research Context & Questions: Ethnic minorities [1] males in higher education are a recent phenomenon. Dating less than half a century ago, and upon adopting a myriad of cultural-nationalist ideologies, ethnic minority students have historically altered the means by which U.S. society conceives the meaning of education and culture. However, despite dominant liberal discourses that views the ascendency of minority bodies in university settings as emblematic of American exceptionalism, might historicizing minority difference via the prism of critical cultural studies provide a more palpable understanding to the means by which neoliberal philosophy has appropriated non-hegemonic conceptions of reality? In other words, is it possible to locate the cultural appropriation of minority student bodies, experiences, and knowledges through the study of university recreational services? Guiding this research hunch is the question: what is the relationship between minority difference, corporate university and the neoliberal marketing/consumption of sports? Have college sports furthered the appropriation of minorities in an effort to bolster the neoliberal university? And if so, does it suggest that student bodies are considered to be corporate intellectual property? What have been the politics of exchange between student activists and student athletes?

[1] For this research project, I will limit my area of study to Black and Latino/Chicano/Hispanic males.

Methodologies:

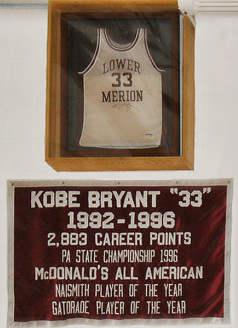

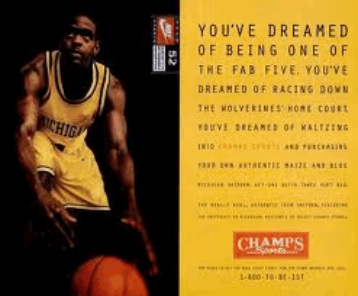

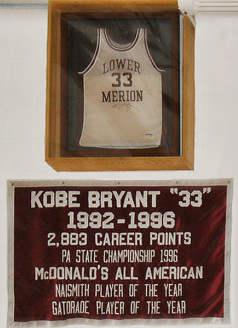

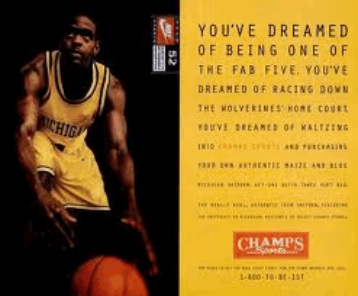

This project seeks to embed critical educational studies, popular cultural studies, sports studies, and political economy. In short, I will be conducting a case-by-case analysis between ethnic minorities, public spaces, and sports entertainment. My methodological framework will [attempt to] provide a critical historiography in the relational positionalities of ethnic minorities and the commodification of their bodies and knowledges. I will conduct discourse analysis of three particular events: 1) San Fernando Valley State College’s 1968 student occupation of the administrators building; 2) Michigan State University’s ‘Fab Five’ 1990’s basketball hype; and 3) Kobe Bryant and the 1996 National Basketball Association draft. By analyzing these three particular historical phenomena, I strive to make evident the evolutionary-representation of students of color in higher education; more significantly, the means by which neoliberal discourse and hegemony have appropriated alternative-potentialities for non-western conceptions of reality.

Hypothesis/Argument:

This research project invokes to further suggest that minority students (ethno-racial) in higher education spaces have been appropriated; specifically, I would like to evidence the claim that within the neoliberal experiment’s marketing of sports, minority students are conceived of to be of a particular kind of intellectual property. While the first half of this research will critically analyze the socio-cultural dimensions of university difference appropriation, the second half of the research project will research how sports have been used as a tool for socio-cultural advancement of minority politics.

Literature Review:

In-class text:

- Boyle, James, Shamans, Software and Spleens (2003).

o Pertaining to intellectual property changes in law within higher education

- Coleman, Gabriella, Coding Freedom: The Ethics and Aesthetics of Hacking (2013).

o Neoliberal and liberal discourses/analysis and the means by which political ruptures can occur within these very frameworks.

- Coombe, Rosemary J., The Cultural Life of Intellectual Properties (2001).

o Appropriation of sports mascots

o Consumption of “the other”

Supplementary text (tentative):

- Bloom, John and Michael Nevin Willard ed., Sports matters: race, recreation, and culture (2002).

- Ferguson, Roderick A., The Reorder of Things: The University and its pedagogies of minority difference (2012).

- Jay, Kathryn, More than just a game: sports in American life since 1945 (2004)

- Shapiro, Harold T., A larger sense of purpose: Higher education and society (2005).

- Sperber, Murray A., Beer and circus: how big-time college sports is crippling undergraduate education (2000)

Okay y’all, so this is where my train of thought has taken me thus far. I’d really like to follow like Coombe and Coleman that despite pervasive structures of exploitation, political resistance occurs. I am hoping to play around with theories of utopia, as well as Deleuze and Guattari’s conception of rhizome. All feedback is very much appreciated. Please and thank you.

Background Information The Indian peasantry is the largest body of surviving small farmers in the world, where two thirds of India makes its living from the land. However, as farming continued to be disconnected from the earth, the biodiversity, and the climate, and linked to global corporations and global markets, and the generosity of the

earth is replaced by the greed of corporations, the viability of small farmers and small farms is destroyed. In 1998, the World Bank's structural adjustment policies forced India to open up its seed sector to global

corporations like Cargill, Monsanto, and Syngenta. The global corporations changed the input economy overnight. Farm saved seeds were replaced by corporate seeds, which needed fertilizers and pesticides and could not be saved. As seed saving is prevented by patents as well as by the engineering of seeds with non-renewable traits, seed has to be bought for every planting season by poor peasants. A free resource available on farms became a commodity which farmers were forced to buy every year. This increases poverty and leads to indebtedness. As debts increase and become unpayable, farmers are compelled to

sell kidneys or even commit suicide. More than 25,000 peasants in India have taken their lives since 1997 when the practice of seed saving was transformed under globalization pressures and multinational seed corporations started to take control of the seed supply. Seed saving gives farmers life. Seed monopolies

rob farmers of life. Research questions With this background as my framework, I intend to apply Boyle's notion of the Romantic author to understand how under globalization Indian farmers are losing their social, cultural, economic identity as a producer and is becoming a "consumer" of costly seeds and costly chemicals sold by powerful global corporations through powerful local elites. This combination is leading to corporate feudalism, the most inhumane, brutal and exploitative convergence of global corporate capitalism and local feudalism, in the face of which the farmer as an individual victim feels helpless. The bureaucratic and technocratic systems of the state are coming to the rescue of the dominant economic interests by blaming the victim. Further, parallel to this dominant discourse of blaming the victim, another counter hegemonic discourse was taking

shape initiated by the suicides by the farmers and lead by activists like Vandana Shiva, Ashok Khosla that is challenging not only the bureaucratic and technocratic systems of the state but also challenging the global power nexus. Some questions that will guide my research are,

What will be the outcome of the dynamics between these two opposite discourses? Can the counter hegemonic discourse challenge the power embedded in the institutions of the society to claim representations for their own values and interests? Will the discord between the two discourses help shape

the new face of the Indian patent law? Methodology I plan to do discourse analysis of news published regarding the counter power revolution. I will look at three mainstream English language national newspapers in India: The Times of India, The Hindu, and The Indian Express from August 2009 to July 2012. I am choosing this time frame as during this time another controversy regarding Monsanto's illegally use of Indian brinjal seeds to create GM seeds came into prominence, that not only triggered country wide uprising, but also compelled the judicial system to reconsider the patent laws. Arguments I argue that just as Castells mentions in his text a counter power is required to challenge the hegemony of the state. It is necessary to stop this war against small farmers and in order to stop this it is necessary to re-write the rules of trade in agriculture. A counter hegemonic movement initiated by Vandana Shiva in India to promote native seeds, is the necessary first step to change our paradigms of food production. Further, I

argue that the very presence of oppositional voices of farmers and activists, constrains the dominant discourse perpetuated by big multinational companies who consider these seeds their "intellectual property" as they own the patents. The study of this contestation is significant to understand if the counter- hegemonic activists are able to bring the discussion of appropriation of native seeds into the public sphere. Authors/Text - In order to understand the phenomenon of the convergence of global corporate capitalism and

local feudalism that initiated the discourse of blame the victim, I intend to

use Gramsci's notion of hegemony. - Further, I will use Balibar's (1991) conception of class racism where he indicated that the phenomenon of institutional racism is attributed in the construction of the category "masses."

- Additionally, I will use Boyle's (1996) notion of the "romantic author" to understand how through the intellectual property rights the identity of an Indian farmer is changed from a producer to a consumer.

- Coleman will help me understand the contribution of the movement through the concepts of free speech can find how meanings of patents can be recoded through it.

- Coombe's "ethics of contingency" helps in thinking about alternative approach of food production. An alternative agriculture is possible and necessary - an agriculture that would protect farmers livelihoods, the earth and its biodiversity and public health.

- I am greatly inspired by Castells' notion of counter power, I hope to use it to understand the uprising of the anti GM seeds movement in India.

I am going into the project from a very wide angel, I am trying hard to narrow my focus, and I hope to get a lot of feed back from you all to help me focus more, any suggestion is most welcome- Thanks Somava

This summer will see the first ever gaming convention that focuses primarily on LGBT issues and community. GaymerX (formerly known as GaymerCon) will be held in San Francisco and will include panels, contests, cosplay, and opportunities for play for LGBT gamers (sometimes called “gaymers”) and their straight allies. Since this is the first convention of its kind, I am interested in how the con’s organizers intend to use the space to address issues pertaining to the games themselves, primarily the representation of LGBT and other characters in games, as well as issues in gaming society, particularly the huge problem of hate speech and bullying. Further, I intend to analyze how GaymerX came to be -- particularly, its use of online technologies to gain popular support and funding through Kickstarter and, as a result of that massive success, the development of of a GaymerConnect app (which allows participants to find and connect to others with similar gaming/geek interests) as well as maintenance through Facebook, Twitter, and the GaymerX website. The use of Kickstarter essentially made corporate sponsorship of this event a non-necessity, allowing the event organizers more autonomy in creating a specific alternative convention (altcon).

Research Questions

Specifically, some of the questions I’d like to ask are as follows:

1) How does the GaymerX event serve as a space of both counterpublicity and counterpower?

2) Will the con be able to discuss and work to implement solutions to the above problems on an institutional level? (This to counteract typically neoliberal proffered solutions by both gaming companies and users, solutions that include anything from self-policing to simply ignoring the problem in the hopes that those who can’t stand the heat will get out of the kitchen.)

3) How will the con offer a safe space to all event-goers? And will the con really be inclusive of all gamers (queer gamers of color, women gamers regardless of sexual orientation, etc.)?

4) How have the event organizers utilized online social networks to build the event, and how does the use of these technologies serve what Castells calls "the autonomy of the social actor"? (7).

5) What is the relationship between the GaymerX event and the general consumer framework of conventions in general?

Methodology

Because I consider this a folkloric event and because it is so very visual, I would like to create a film about the con. As a documentary setup, I would include not only footage from the con (floor action, panels, contests and community get-togethers) but also interviews with attendees and event organizers. The fieldwork would be combined with theoretical grounding that comes from the fields of American Studies, digital technology studies, leisure studies (game theory), queer theory and folklore, at least. As a queer gamer, I have an emic perspective on this subject, and so my challenge (as always) is to strive for as much reflexivity as possible and to consider the experience from an etic perspective, as well.

Argument

My hypothesis is that the event organizers are really looking to transform the convention space – from a potentially unsafe space consisting of “booth babes,” overly judgmental cosplay, and panels that neglect or only pay lip service to LGBT issues in gaming to one that that celebrates the queer gamer/geek, strives for inclusivity for all, and really attempts to bring awareness to the very real social problems that accompany these sorts of leisure activities. The need for this kind of awareness is important particularly for a generation where “everybody games,” which is the GaymerX motto. It’s not literally true, of course, but video game culture has become more mainstream than ever and serves as a primary source of recreation for many young people. In this visual/online culture, the chances of being exposed to hate speech and misrepresentation of LGBT communities have multiplied greatly, so the idea of creating a safe space for “gaymers” (particularly young gaymers) is significant.

One argument I’d like to make pertains to the social value of altcons such as these to bring publicity to an area that some people tend to dismiss as “frivolous.” But it is precisely because gaming is perceived mainly as “play” that it becomes important as an area of study and transformative power, however. In folklore, “ludic recombination” is an integral part of any ritual, for through play people learn the social mores of their communities. If in gaming people learn that epithets against race, gender, sexuality, ability, etc. are acceptable, or they are exposed to stereotypical representations of LGBT people, racial minorities, indigenous peoples, and women, then these are carried into other parts of their lives. Further, the anonymity provided by the Internet allows for the perpetuation of biases and makes hateful speech easier to get away with and harder to police.

I am hoping that how this con uses its space will help find ways of fighting these issues beyond the individual, forcing gaming companies to change their policies with regard to hate speech as well as include representations of LGBT peoples and other less dominant groups that are less stereotypically racist and/or misogynistic. This con has the opportunity to demonstrate to gaming companies that tolerating hate speech and creating racist/sexist/ableist misrepresentations in their games and at other gaming conventions is unacceptable because it DOES impact how people operate outside of these leisure frameworks.

Authors/Texts

Thus far, Coombe’s discussion of counterpublicity and how it operates is useful in informing I would approach the con as having a specific political agenda. I am also interested in Castells discussion about networks of power and how they operate, and I would like to discover how the con is a practical application of those ideas. I’m hoping that perhaps others in the class will have recommendations for expanding my theoretical framework?

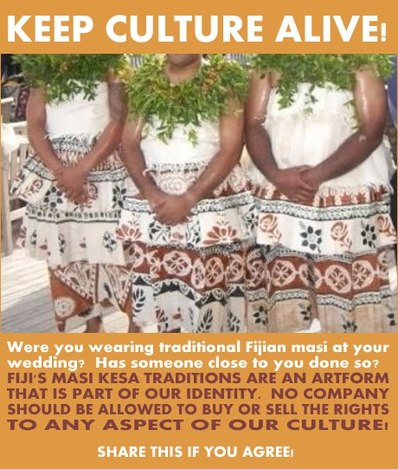

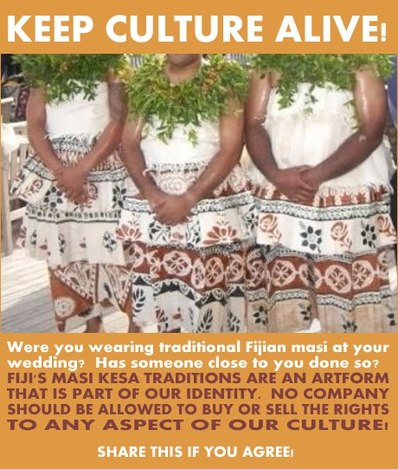

We support and applaud Air Pacific for choosing to use masi motifs on the new Fiji Airways fleet. We are proud that our culture is being showcased to the world. But we don't support Air Pacific's application to trademark these motifs. These cultural motifs are used in masi making, mat-weaving, wood-carving and by other artisans and craftspeople. These motifs were not created by Air Pacific and have been handed down over the generations. The trademark means that masi makers, carvers, weavers and our craftspeople will have to ask permission from Air Pacific if they want to use these masi motifs or draudrau in future. Do more than just making a comment on facebook - be heard, sign the petition, write a letter and get more signatures friends. The petition is online here

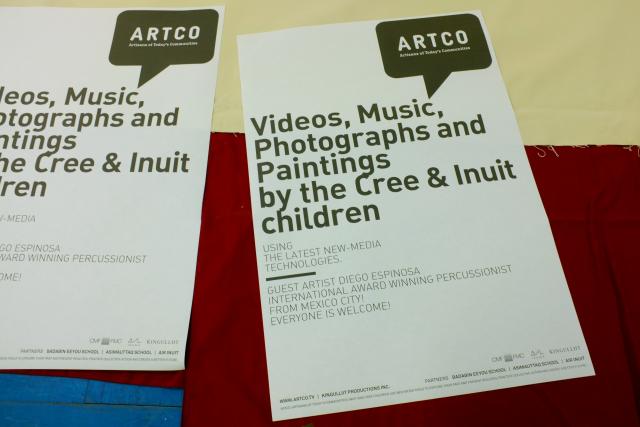

ARTCO is a project designed for mobile devices in communities with low-speed internet connections.

Research Questions

In popular culture the Latina body is often commodified as a consumable hyper-sexual curvy body that is strategically homogenized in order to reproduce ideals of whiteness, while simultaneously representing an exotic foreignness. In the media, the homogenized Latina body is not white, but does reproduce Eurocentric ideals of beauty—in both English and Spanish media outlets—often for capitalist demands. This of course requires a critical understanding of the history of colonialism in both Latin America and the Caribbean, in addition to an evaluation of the ways these histories get played out in the U.S., which as we know has its own racial discourse. Which brings me to my next point, in 2008 when Barack Obama received the presidential nomination we began to surprisingly see a new sense of visibility of black Latina bodies in U.S. popular culture. Popular magazines like Latina were now celebrating Afro-Latinas and were dedicating monthly issues to Afro-Latina/o culture. However, like any subculture that gets acculturated in the dominant imaginary, Afro-Latina bodies were subjected to commodification and homogenization. Today, our nations multicultural, bicultural and interracial explosion is undeniably influencing political discourses of race in the U.S., but what are these new portrayals of Latinidad—specifically, Afro-Latinas—telling us about how the African Diaspora is being represented in magazines such as Latina, or most important, how do readers consume these representations? Are consumers resisting Latina magazines homogenization of Afro-Latina bodies? For that reason, I find it important to look at social media spaces like Tumblr and Instagram in order to examine how counter-hegemonic resistance looks like within those sites.

Methodology

My methodology will include a theoretical breakdown of the homogenized Latina body in the media and its relationship to capitalist demands. In order to mobilize this connection, I will also need to ground myself in the theoretical conversations that scholars are having in fields like Latina/o Studies, Chicana/o Studies, Cultural Studies, and American Studies regarding popular culture representations of the Latina body, and the effects these representations have on the material reality of Latin@s in the U.S. today. In addition, I will examine the magazine, Latina and their representations of Afro-Latinidad. I will specifically focus on the 2008 to 2012 editions, which will include an in depth analysis of both the online website and the hard cover magazine. Moreover, I will also look at Tumblr and Instagram in order to trace alternative representations of the Afro-Latina body in order to identify the voices that are resisting the coorporatization of Latina bodies in the media.

Argument

I do not want to completely reject Latina magazine in my analysis because I do believe that the magazine is making some important contributions to the Latina community, however we must always be mindful of what we are consuming. Coombe talks about the ways cultural hegemony is historically constructed through Eurocentric discourses of power, which speak directly to Latina magazine’s relationship to commodification, because although it is a magazine targeted for Latina women, the magazine must consent to commodification and to some extent cultural appropriation in order to successfully participate in capitalist demands. Therefore, is Latina magazine both a hegemonic and a counter-hegemonic production? If whiteness is understood as an ideological process, Latina unveils the social, cultural, political, and economic dangers of the Latin@ community, when fetishizing the Latina body as one that is consumable only when it poses no real threat to whiteness in mass-media productions. For that reason, I hope to suggest that counter-hegemony can be politically mobilizing when Afro-Latinas themselves not only reject the essentialized notions of Afro-Latinidad represented by the media, but in doing so, offer alternative representations of Afro-Latinidad that not only subvert western conceptions of ideal beauty, but also rupture the historical relationship between whiteness and “foreign-ness” that often gets played in the Latina body, especially in popular culture.

Authors/Texts

So far, Coombe’s theoretical framework is extremely useful for my own individual research project because she not only addresses the role of whiteness and hegemony in technology driven spaces, but also provides critical analysis of alternative representations of resistance that challenge and subvert ideological processes. I also think Coleman will be useful in my navigation of Afro-Latinas as subculture within the Latin@ imaginary, especially when examining how they simultaneously play themselves out in the public sphere. Coleman’s chapter of “Code is Speech” will be influential to my analysis of Tumblr and Instagram, since I will read these spaces as spaces that allow counter-hegemonic resistance for Afro-Latinas, specifically when thinking about the ways they decide to subvert Latina magazine's representations of black Latina bodies in the media, which will I will argue speak to their own “type of freedom” (Coleman 133).

This is still a work in progress and I am completely aware that my own research can change at any time, therefore I welcome any constructive criticism that I hope will help me mobilize this topic to its fullest potential. Thank You!

The President of the United States, Barack Obama, has recently been given tremendous powers to conduct cyber-warfare against percieved cyber-threats in a secret program involving the Pentagon and the National Security Administration, the CIA and the FBI. My research proposal will deal with this new paradigm in terms of neo-liberalism, liberty, and freedom of speech as interregated by the authors used in the class. A large cohort of government hackers will be mining the internet for data concerning international F/OSS hackers. The loose doctrine of pre-emptive strikes that is used to justify the secret drone strikes and assassinations taking place in Pakistan, Somalia, Yemen, and Iran, (anywhere the President deems a threat to United States security interests) will be employed to rationalize cyber-warfare of possibly nuclear proportions against any percieved enemy. I am interested in the ethical ramifications of such warfare.

Questions guiding this research will include Why this is happening? Just What is happening? Who does this affect? and Where will this lead the United States in the future? How does this effect our ethical identification as "Americans"? Is this a moral way to conduct ourselves as a nation? Methodology will include a literature review, internet mining, and possibly interview with other researchers. I argue that cyber-warfare as pre-emptive strike should be overseen by a watchdog branch of the government in order to provide proper ethical review before involving the United States in cyber-war, its repercussions, and possible side effects on our economy, our liberty, and our freedoms. Boyle, Coombe and Coleman, with Castells will guide me in exploring this subject.

So, I’m really struggling here to imagine the intended audience for my project. Cultural studies as a field is new to me and I don’t quite understand what is considered acceptable in terms of research questions or methodologies after reading our three books. The project idea below is based on my thesis, but starts with an issue I mention in passing (how teaching copyright and fair use might provide an opportunity for reframing plagiarism) and takes it up it as the focus of a new project. While I am not “rehearsing my project from my initial vantage point,” I am clearly dealing with issues that are deemed important within my particular scholarly community, which I think is acceptable. However, I am not sure if I am approaching the issues from a cultural studies perspective. Basically what I am trying to say is that any feedback or guidance you could provide would be very much appreciated. In particular, let me know if you could think of anything in the way of methodology or additional texts (keep in mind that I haven’t read what everyone else read last semester in 506 but could/should draw on those texts). Thanks to everyone in advance for helping out this slightly disoriented Rhet/Comp person : )

Research Questions - Currently, instructors and university administrators approach plagiarism through the rhetoric of fear and punishment. This approach has negative pedagogical implications for students because it further mystifies academic writing, glosses over the diversity of values and practices surrounding source use both in and outside of academia, conflicts with our goals as educators, and fails to prepare to students to use sources effectively in future writing contexts. How can instructors and university administrators move past this reductive and problematic approach to plagiarism? How might we reframe our understanding of plagiarism to make room for more effective and theoretically sound teaching practices?

- In disciplines across the curriculum, the conception of “writing” is expanding from a limited notion of words on a page to include other mediums of communication beyond the linguistic. Students now “compose” texts with images, audio, and video. Given that this expanded notion of writing suggests the need to teach students about copyright and fair use, how might the introduction of these new concepts provide us with an opportunity to reframe (or recode) conceptions of and educational approaches to plagiarism?

Methods - This project would involve the study of ten writing courses and would produce a detailed, multilayered set of data for analysis. Five of the classes would be traditional writing courses that don’t ask students to go beyond “the written word” in their compositions and don’t introduce concepts of copyright or fair use. The other five courses would assign students to “compose” texts with some mix of images, video, and/or audio and would introduce concepts of fair use and copyright.

- Types of data to be collected: Course materials, including plagiarism statements, handouts, and assignment sheets; recordings and notes from class meetings where plagiarism, copyright, or fair use are discussed; recorded interviews with students and instructors; copies of student work; records of any disciplinary action taken against students.

- Data analysis: I will conduct a discourse analysis of all collected materials. I will make several passes through the materials, focusing on instances that are connected to source use, plagiarism, fair use, or copyright. I will use key words and metaphors to identify and then code various “frames” for talking about or indicating intellectual property. Once coded, I will look for patterns between the two sets of classes and draw conclusions based on my findings.

Argument - My hypothesis is that the concepts of intellectual property, copyright, and fair use provide an opportunity for teachers, administrators, and students to reframe and rethink our understandings of plagiarism and source use. My study is designed to see if there is evidence of this happening in classes that teach students about copyright and fair use. It is possible that I find that concepts such as copyright (although they contain the possibility to reframe approaches to plagiarism) might instead be folded under and presented to students in educational contexts through the dominant frames and narratives of plagiarism.

Texts - Coleman, Coding Freedom. Coleman’s ethnographic study of how F/OSS hackers recode the meaning of intellectual property through concepts of free speech (thus critiquing liberalism from within liberalism) would provide a nice framework for me to consider how we might recode the meaning of plagiarism through concepts of copyright and fair use. In particular, the inflexible, black-and-white conception we have of plagiarism (at least in the dominant frame or narrative) is incongruous with the dominant discourse around fair use and copyright, which are more openly acknowledged as sites of contention and change. In other words, although plagiarism and copyright both operate through the notion of romantic authorship, the controversies within copyright law point to fractures within the ideologies surrounding intellectual property issues. It may be possible to take advantage of these cracks in our ideological approach to intellectual property in order to recode/reframe plagiarism.

- Boyle, Shamans, Software, and Spleens. I can link up Boyle’s discussion of copyright and romantic authorship to the ways in which romantic authorship frames the dominant frames/narratives of plagiarism.

- Coombe, The Cultural Life of Intellectual Properties. Coombe’s notion of the “ethics of contingency” provides an alternative frame for thinking about issues of plagiarism – one that emphasizes the importance of context over a static set of rules.

- Gramsci. Of all the texts listed on the 506 syllabus, Gramsci seems the most promising for my project. Perhaps I can draw upon his theories of education and social change?

- Additional: key texts from Andrea Lunsford and Rebecca Moore Howard, scholars in composition studies who have written extensively on issues related to plagiarism and intellectual property. I am already familiar with this scholarship from work on my thesis.

Since we talked briefly about Anonymous' #OpThunderbird project last week (btw you can check out on Twitter at #opthunderbird, #mmiw, & #missingsismap), I thought I'd pass on a link to its affiliate Missing Sisters project. As I mentioned earlier, #OpThunderbird is in solidarity with the thousands of missing, murdered, & sexually assaulted Native women (which both Canada & the US continue to ignore and marginalize)...the Canadian government, for example, acknowledges that there are about 500 missing Aboriginal women, when the real number is somewhere around 4000. Missing Sisters is mapping cases of missing, murdered, & sexually assaulted Native women (on both sides of the border)--you can check out their map here. The people running it are very methodical—once they get a report submission, they look up news articles, photos…basically everything they can on the woman the report is about (regardless of case status), so as to have a detailed account of the woman and her story (that’s why it’s taking so long to get all the reports up). After only 2 days, it's already at 50 verified reports, though they have several hundred pending (8 solved murders; 20 unsolved murders; 21 unsolved missing; 1 unsolved sexual assault). I would really urge people to go check out the project, pass the info on, and submit if you know of anyone whose story should be on the map (they take anon submissions!)…even if you don’t submit a report, there’s a lot to learn from the reports posted thus far, and you could be keeping an eye out for some of the 21 missing women posted thus far. I'm thinking this could also be prescient for our upcoming discussion of Castells!

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed